A Lead Seal and a Dead Man's Bones

My last post was about the 1,137th anniversary of Arnulf becoming king. This post is about the 1,225th anniversary of his death. It may sound surprising that the date of Arnulf’s death, and where he was buried, has multiple possibilities. This is a king after all, shouldn’t we know these things? Modern historians confidently know the answer to this question (December 8th at St. Emmeram’s in Regensburg),1 but one medieval contemporary, Regino, was evidently not so well-informed. This is an important point when reading medieval, or really any pre-internet source: we need to understand the limitations on their access to information. I can call up hundreds of digitized mansucripts at my fingertips, plus countless editions of medieval texts, in a way that no medieval author could do. This is not to say they didn’t care about the truth, as I hope to show here.

The first account of Arnulf’s death, the near contemporary Annals of Fulda, actually gives us the correct burial location: St. Emmeram’s monastery in the Bavarian town of Regensburg.

The emperor closed the last day [of his life] in the city of Regensburg and was buried by his men in honor in the house of the blessed Saint Emmeram, martyr of Christ.2

Notably this does not give us a date for his death, only where he was buried. On the other hand Regino, the former abbot of the important Carolingian monastery of Prüm, has a completely different account:

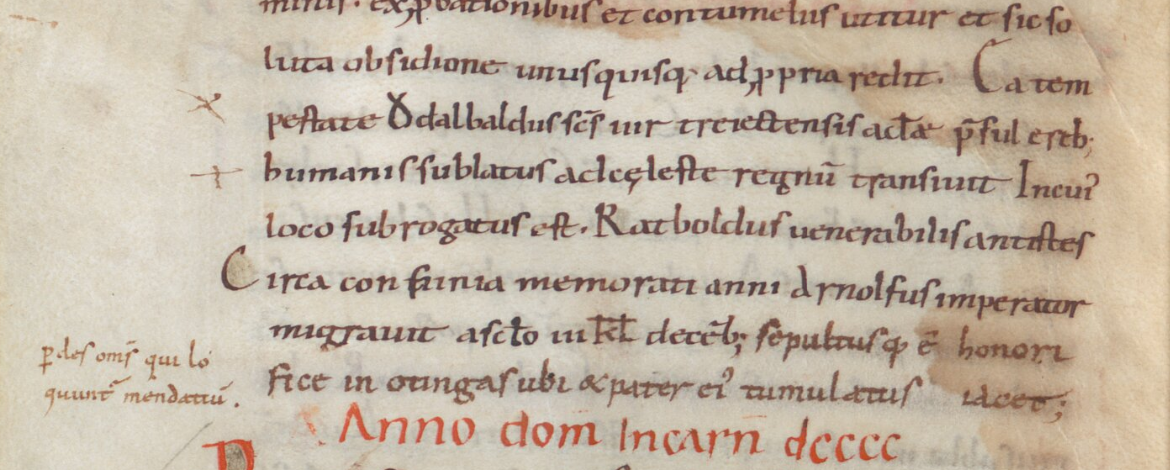

Around the end of the recollected year the emperor Arnulf departed from the world on the third day before the Kalends of December and was buried with honor in Ötting, where his father lay having been buried.3

Regino not only gives us the incorrect date (November 29th when we convert the Roman dating) but also the incorrect place of burial. Regino was writing only a few years after Arnulf’s death, and was ostensibly writing for Arnulf’s son, so the inaccuracy here is a bit odd. Regino was based in Trier, however, quite a ways away from Regensburg and thus may have heard this information second-hand, filtered through others. At the same time, it makes entirely plausible sense that Arnulf would be buried next to his father: there were already several sites that had multiple Carolingian burials. Both Louis the German and Louis the Younger were buried at Lorsch, while the abbey of St. Arnulf (no this is not an accident they share a name) in Metz also served as a sort of Carolingian mausoleum.4

Evidently already in the middle ages people were skeptical of Regino’s account. In a tenth century manuscript from Freising we find a marginal notation to his passage quoting Psalm 5: “you [as in, God] will ruin all who utter lies.”5 A strong criticism indeed!

We know that later readers of Regino also seem to have had an issue with his account. Some variants of the text actually include the correct place of birth in this passage: “[he] was buried in honor in Regensburg in the basilica of St. Emmeram the martyr, where himself, while he resides [there], is venerated by many.”6 Unfortunately, none of these manuscripts appear to be digitized, so I cannot see how they are actually placed in the manuscript or what has been removed.7 Regardless, people seem to have known Regino was incorrect. In some cases, it appears clear that readers of Regino had actually been to Arnulf’s tomb in St. Emmeram, proving that he was buried there. Otto of Freising, writing in the 12th century, in fact quotes Regino about where Arnulf was buried. However, he notes, “his coffin is displayed in the monastery of the blessed Emmeram in Regensburg.”8 Otto then tries to square this obvious problem by suggesting “that having been buried there he was transferred a short while later.”9 Others simply ignore Regino’s account entirely, and simply note him being buried in St. Emmeram’s.

All of this makes it clear that Regino was in the wrong, and Arnulf was in fact buried at St. Emmeram’s. Yet it does little for the date of Arnulf’s death. The 15th century necrology from St. Emmeram in fact notes his death on November 27th, while noting that Arnulf was “the founder of this place.”10 There is another necrology, contained in Bernold of Constance’s Chronicon, that notes Arnulf’s death on December 8th. Curiously, this appears to be an autograph copy by Bernold.11

These two questions: where and when, are neatly summarized by an event in the 17th century. In 1642 the monastery of St. Emmeram had suffered a fire, which had evidently destroyed the location of Arnulf’s grave. Almost 30 years later, in 1671 while repairing the church, they discovered Arnulf’s tomb and decided to open the sacrophagus. The abbot, Coelestin Vogl, helpfully wrote down what he saw in a report published in 1672. While restoring the bones and replacing them, the abbot discovered a lead seal “under the head” with an inscription that read:

VI IDUS DECEMBRIS ARNOLT IMPERATOR OBIIT.12

That is, “Emperor Arnulf died on December 8th.”

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.

I owe much of the impetus for this to F. Fuchs, “Arnolfs Tod, Begräbnis und Memoria,” in Fuchs and Schmid (ed.), Kaiser Arnolf, pp. 416-434, which first turned me on to much of these smaller pieces of evidence. ↩

AF (B), s.a. 900, p. 133-134: Imperator urbe Radaspona diem ultimum clausit et honorifice in domo sancti Emmerammi martyris Christi a suis sepelitur. ↩

Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 899, p. 147: Circa confinia memorati anni Arnulfus imperator migravit a seculo III. Kal. Decembris sepultusque est honorifice in Odingas, ubi et pater eius tumulatus iacet. ↩

The thing to read for an overview is J. Nelson, “Carolingian Royal Funerals,” in F. Theuws and J. Nelson (eds), Rituals of Power: From Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages (Leiden, 2000), pp. 131-184 esp. pp. 166-169. For St. Arnulf in Metz specifically M. Gaillard, “L'éphémère promotion d'un mausolée dynastique: la sépulture de Louis le Pieux à Saint-Arnoul de Metz,” Médiévales 16, no. 33 (1997): 141-151. ↩

BSB Clm 6388, fol. 179v: perdes omnes qui loquuntur mendatium. ↩

Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 899, p. 147 includes this variant reading for certain manuscripts: in Radispona in basilica sancti Emmerami martyris, quem ipse, dum vixit, multum veneratus est. ↩

They are Vienna Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, cod. 538, 639, and 3522 according to the editor. ↩

Otto, Chronica, MGH SS rer. Germ. 45, p. 274: Monstratur tamen sepulchrum eius in monasterio beati Emmerami Ratisponae. ↩

Otto, Chronica, p. 274: ut ibi humatus huc postmodum transferretur. ↩

MGH Necr. 3, p. 331: fundator huius loci. ↩

Bayerische Staatsbibliothek Clm 432, fol. 7r. Accessible here: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00039847?page=,1 ↩

C. Vogl, Mausoleum Oder Herrliches Grab, Deß Bayrischen Apostels und Blut-Zeugens Christi S. Emmerami (1672), pp. 62-63. Accessible here: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Mausoleum_Oder_Herrliches_Grab_De%C3%9F_Bayr/m6JRAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1. The seal is probably not 9th century, see Fuchs, “Arnolfs Tod,” pp. 432-433. ↩