A Medieval National Convention?

Assemblies, Ritual, and Political Communication

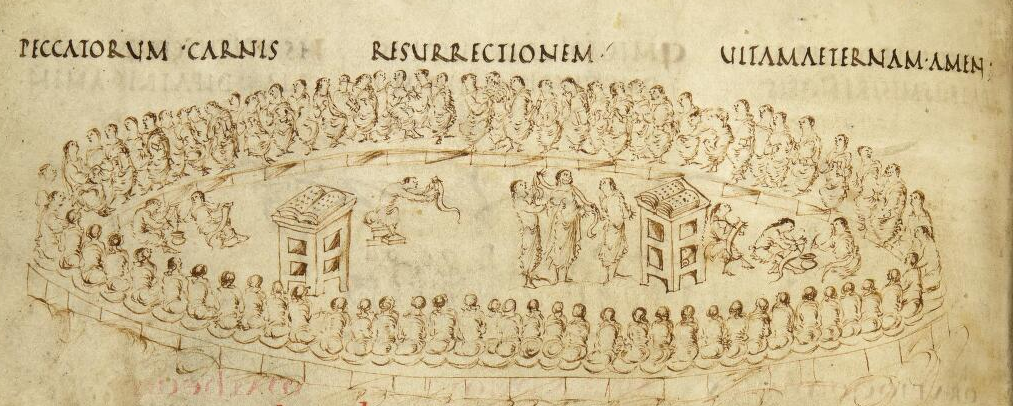

Recently I have been working on Arnulf’s self-presentation as a ruler, in particular between the years 894 and 896. It was during this period that I believe Arnulf and his court began to espouse a more imperial conception of Arnulf’s kingship that portrayed him as a ruler above his contemporaries. The venue for these displays of superiority were royal assembles. Assemblies, as Timothy Reuter wrote, were the moments when the entire political community of the kingdom came together as one body.1 Often assemblies were staged to showcase the consensus and harmony of the political community, and were useful for promoting royal legislation, receiving embassies from far away places, and resolving any political disputes within the realm. In other words, they were useful venues for displays of authority. Rituals could be useful for articulating the political order and communicating the status of the participants. Reuter himself noted the similarity to modern political events, especially in their staged nature.

This is the context for the assembly Arnulf held at Worms in June 895. Arnulf had been distressed to hear news from West Francia of the conflict between Odo, the non-Carolingian king that Arnulf had sanctioned in 888, and Charles the Simple, the young son of a Carolingian king who had been crowned at Reims in early 893 and who received Arnulf’s blessing in 894. Arnulf “ordered that Odo and Charles should come to him, where he would end the evil of so great a misfortune between them.”2 Odo would actually make it to Worms, while Charles wanted to go but dispatched a messenger instead. At the assembly Arnulf evidently once again supported Odo, and Charles’ messenger seems not to have made it in time. At the same assembly Arnulf made his own son, Zwentibald, king of Lotharingia. The Annales Vedastini indicates specifically that this was done “in the presence of king Odo.”3

This is a pretty nifty bit of stage managing if we understand it correctly. That is, Arnulf intended to demonstrate his own mastery over other rulers, and to do so he intended to have two kings of West Francia come to him and submit to his judgment over the dispute. While these two kings were there, Arnulf was going to elevate his own son as a king of Lotharingia, which had not had its own king since 869. The effect of such an assembly would have been to assert Arnulf’s superiority and hegemonic position over these places. In other words, a somewhat imperial presentation of a ruler who is elevated and distinct from these kings. This did not happen exactly as Arnulf planned because Charles the Simple did not come to the assembly. But the overall impression would have still been maintained with Odo coming to the assembly bringing gifts and witnessing Zwentibald becoming king.

But why would Arnulf go back and forth in supporting first Odo, then Charles, and then Odo again? Regardless of who he supported, it seems to have done little to end the conflict. Perhaps a more compelling explanation for the flip-flopping is that Arnulf was directing a message at both Odo and Charles, but more importantly, an internal audience.4 That is, there was no coherent policy of favoring one party or the other, but instead the goal was to demonstrate Arnulf’s superiority as a source of legitimacy and moral judgment. As long as Odo and Charles continued to travel to Arnulf to seek his sanctioning, it would have reinforced Arnulf’s credibility as a leader of superior status. Whether Arnulf had the ability to actually influence the conflict was less important than the symbolic role he played, and one which both Odo and Charles seem to have believed in fervently. The oscillating support suggests, to me, that Arnulf was presenting this image of superiority above all to an internal audience of his own elites.

It is here that I find the upcoming Democratic National Convention on my mind. There are, of course, differences between medieval assemblies and modern political conventions. However, they both serve somewhat similar functions as vehicles for political communication. Both a medieval assembly and a modern convention are meant to demonstrate the internal unity and cohesion of the political community. In the medieval context this meant the elite of the kingdom, in the modern context it means the political party. Both events thus have largely internal audiences. Political conventions are meant to showcase unity and, theoretically, provide the party platforms, but for the most part they are about the party and its organization, fundraising, and to present the rising stars of the party to this internal audience. Indeed contested conventions are largely a thing of the past, and viewership numbers have been declining with even the aftermath of Trump’s assassination attempt unable to get people to tune in.

Yet it is here that the modern actually makes me ask new questions of the medieval. Just as there are people who only intermittently follow the convention, where there elites who did not attend the assembly but followed along from elsewhere? Or were only semi-engaged with them? We tend to think of elites as either in or out of favor, but not usually do we think about disengaged elites. Were there “low-information” elites in the Carolingian world? There must have been counts out there who saw themselves as part of the bigger political community, but had little interest in attending assemblies or interacting with royal agents.

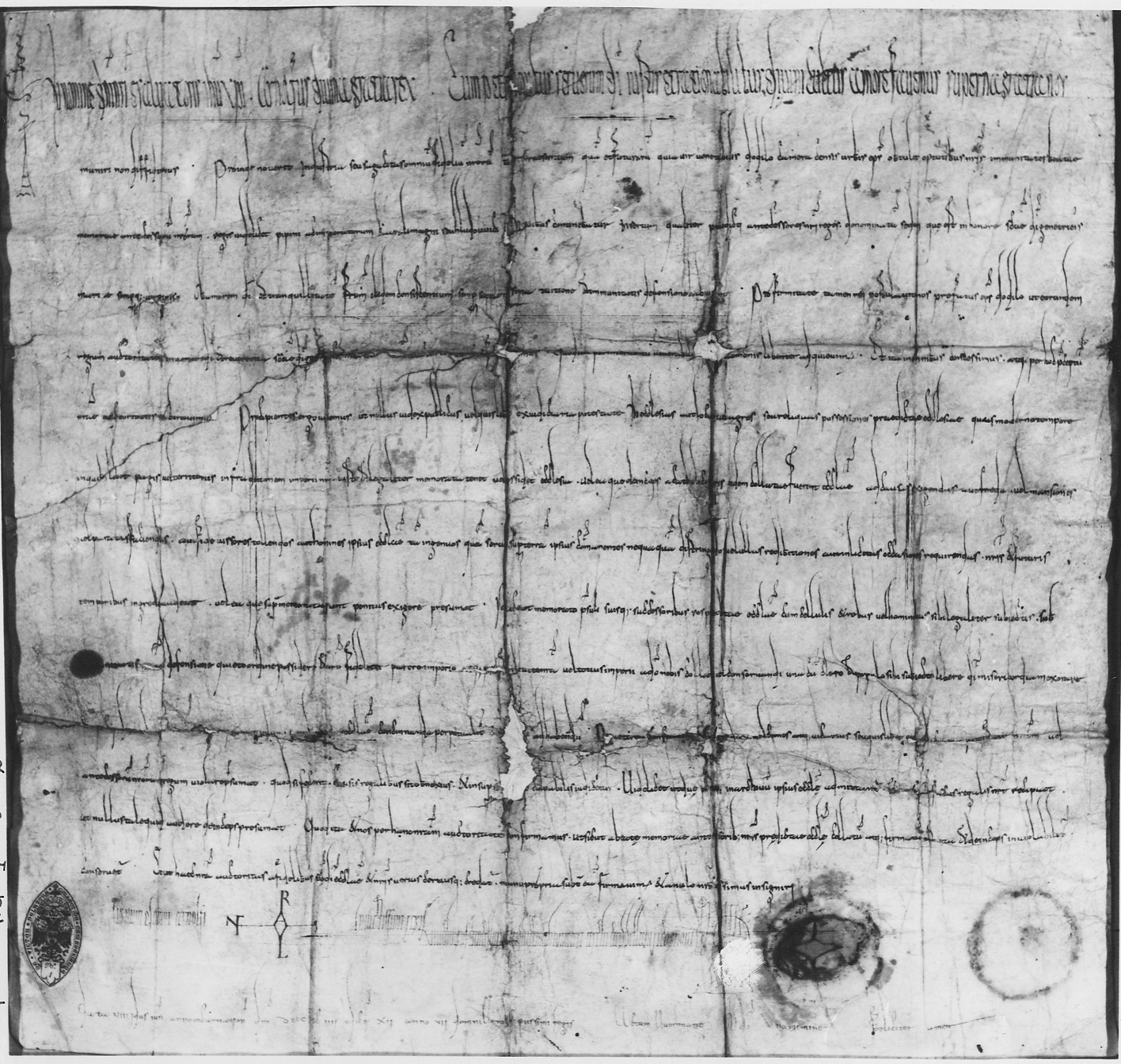

In a similar vein, we saw the intense debates around Joe Biden and the crisis that might have caused at the Democratic National Convention. Disordered conventions had serious consequences, one needs to only think about the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Were there similar types of debates going on behind the scenes before our medieval assemblies? Negotiations must have been taking place to smooth over concerns ahead of time, and contemporaries were shocked when things didn’t go according to plans. In 888 when Arnulf had first summoned Odo to him, Odo sent along a delegation of men to discuss matters with Arnulf before his arrival.5 We don’t know what this discussion entailed, or how well known such discussions were. What it does suggest is that for most of these events there was negotiation beforehand. In another case we can catch a glimpse of this from Charles’ perspective. When Charles the Simple came to Arnulf in 894 the bishop of Cambrai, Dodilo, came along with the king. We know this because Dodilo received a charter from Arnulf, and this charter was mostly written by a West Frankish scribe.6 This suggests that Dodilo was relatively confident the grant would be approved by the king, and it was brought to the assembly where Arnulf’s scribe then added the details at the end of the charter including the date and place. Perhaps Dodilo had been operating as a go-between for Charles the Simple and Arnulf, and was rewarded for his efforts with a charter.

This is all to say that I have a new understanding of both modern political conventions and medieval assemblies. They were events directed at internal cohesion and which gave an opportunity for the political community to exist in one place as a collective whole. They were also about articulating political hierarchies. In the case of the assembly with the king at the top, and in Arnulf’s case as I think I have shown, over other rulers as well. In the case of a political convention the goal is to cement the status of the nominee as the ostensible leader of the party, and denoting those who are following in their footsteps as rising stars by giving them speaking chances, etc. There was much debate and negotiation that went into these events, precisely because the impression of unity and consensus was important to these internal audiences. It is not that they are simply “choreographed” and unimportant, but that audiences expected this type of unity. Anything else reflects poorly. The DNC will likely be watched closely to see if Joe Biden speaks, as he is believed to be, as well as if anyone opposes Harris’ nomination. A “smooth” convention will reaffirm the new hierarchy of the party, and highlight to the party itself that they are rallying around their candidate.

This was perhaps a bit more rambling than usual, but hopefully it provides an interesting counter point to political commentators that see the conventions as somewhat pointless exercises in scripted TV moments. That may very well be true, but understanding them as political rituals allows us to see them as more functional and sophisticated. We do not need to accept that anything that appears uneventful was pointless. Instead, understanding political communication helps us to understand that even the most uneventful political rituals were built on negotiation, consensus, and political power.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

T. Reuter, “Assembly Politics in Western Europe from the Eighth Century to the Twelfth,” in J. Nelson (ed.), Medieval Polities and Modern Mentalities. ↩

AV, s.a. 895, p. 75: ut Odo et Karolus ad eum venirent, quatinus tantae calamitatis malum inter eos finiret. ↩

AV, s.a. 895, p. 75: in praesentia Odoni regis. ↩

I am also indebted to S. Ottewill-Soulsby’s wonderful book The Emperor and the Elephant for the idea that certain types of diplomacy have a more internal purpose. ↩

AV, s.a. 888, p. 65. ↩

D A 127. ↩