Bastard, Usurper, King

"Illegitimate" sons and political destiny

One of the most common images of the middle ages in the public imagination is the bastard son. Many movies, TV shows, and books feature these sons who are disqualified from inheritance because they are not legitimately born. Indeed, the Wiki for Game of Thrones even has an entire page specifically on legitimizing bastards.1 If there is one word used to describe Arnulf, it is probably either bastard or illegitimate. Very often this may be the only piece of information noted about him in short biographies, comments, and references in modern historical scholarship. Last week I briefly discussed the challenge Arnulf made to his uncle Louis the Younger in 879. Historians have often linked Arnulf’s political destiny to his birth status, arguing that this illegitimacy in effect “disqualified” him from becoming king. One historian even argued that Arnulf must have been “content” to not become king in the 880s because he knew his birth status made it impossible. This thus leads to two interconnected questions: first, what is our evidence for Arnulf’s illegitimacy? Second, did this disqualify him from becoming king? I am not arguing that contemporaries believed Arnulf was a fully legitimate son. Instead, what I will suggest is that contemporaries considered illegitimacy as only one factor among others. Because this is a bigger, and more involved topic, it is a bit longer than the other posts. If you want to read more, you can find an entire chapter essentially dedicated to this in my dissertation.

Any brief examination of the names of Carolingian rulers would quickly expose Arnulf as an outlier in a field of Pippins, Charleses, Louises, and Carlomans.2 Arnulf’s success itself distinguished him from many of the illegitimate, not to mention legitimate, Carolingian sons who revolted in the eighth and ninth centuries. This success makes historians suspicious of sources that ignore or downplay his illegitimacy, seeing them as justifying his takeover in 887.

That only one source mentions Arnulf’s illegitimacy explicitly is the first sign of something odd going on. The source, from the West Frankish kingdom (that is, not where Arnulf would eventually become king) notes his birth status in relation to him battling with his uncle in Bavaria in 879. The author of this text was the Archbishop of Reims Hincmar, a prolific author who himself had been involved in the bitter marriage dispute of the Carolingian king Lothar II.3 If anyone was going to make a big deal about birth status, it was Hincmar. The other sources pass over Arnulf’s birth status in silence. Some, like the East Frankish Annals of Fulda, point out that Arnulf’s children were born from concubines, but Arnulf himself is simply “the son of King Carloman.”

This would appear to be a point in favor of it being a deliberate omission to justify the coup in 887, but the main problem with all these interpretations is that they assume that birth legitimacy functions similarly across time and that being illegitimate was the only factor to disqualify someone from becoming king. Yet there were plenty of legitimate Carolingian sons who did not succeed in their revolts too, so we cannot necessarily attribute the failure of Arnulf in 879 exclusively to that. What becomes clear upon reading the sources is that contemporaries viewed Arnulf primarily through his relationship to his father, and in some cases his grandfather. Notker, a monk at the monastery of St. Gall, would note that Arnulf was from “the fertile root of Louis [the German]” and in a different text saw him as one of the hopes of the Carolingian dynasty:

“[Arnulf] still lives, and oh that I wish he would live! Lest the lamp of the great Louis [the German] be extinguished from the house of the Lord!”4

Arnulf’s claim, according to Notker, was grounded in his dynastic status, as a descendant of Louis the German, more than his specific familial status as a “legitimate” son. It is important that Notker was writing before Arnulf became king in 887. If all of our sources were written after 887 it would be logical to conclude that they were simply trying to justify events that had already occurred. That Notker wrote before 887 highlights that this is not necessarily true, and suggests that contemporaries were able to understand birth status and familial status in a complex way.

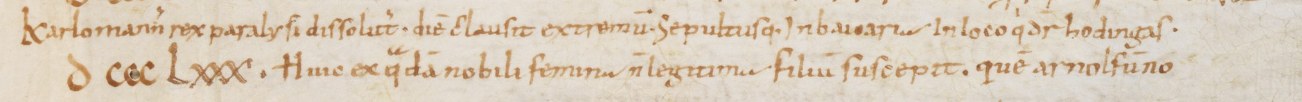

We can even see the process of hardening when it came to attitudes around illegitimate sons by looking at a revision of a text. Regino was writing a chronicle in the early tenth century, after Arnulf was dead, for the bishop Adalbero of Augsburg, the spiritual pater of Arnulf’s young son Louis (r. 899 to 911). Regino notes that Carloman had no children from “legitimate marriage” but instead had a son from a noblewoman on account of the barrenness of his marriage.5 In the late tenth century, so a little less than a hundred years later, the Annales Einsiedelnses borrowed heavily from Regino, including the passage describing Arnulf. The entry for 880 copies almost verbatim the line about Arnulf’s birth except that the Einsiedeln annalist exchanged the phrase describing Arnulf, elegantissimae speciei (“of the most elegant appearance”), with non legitimum (“illegitimate”). The Einsiedeln annalist therefore changed the sentence to emphasize that Carloman “received an illegitimate son from a certain noblewoman” instead of Regino’s “he received a son of the most elegant appearance from a certain noblewoman.” By the 990s Arnulf was now able to be explicitly defined as an illegitimate son; when Regino was writing, close to Arnulf’s own life, contemporaries may not have had as strict of an understanding of birth legitimacy. Arnulf may have also benefited from his birth status not being publicly affirmed in the way that other illegitimate Carolingians were. That is, there was no attempt by his father to legitimize him like had happened with Charles the Fat’s illegitimate son Bernard. As such Arnulf may have enjoyed a bit of ambiguity. Paraodoxically, then, an attempt to legitimize a son could instead solidify their illegitimate status.

Perhaps a better way of approaching the question is that despite their illegitimacy, Arnulf and Bernard both possessed a degree of “Carolingian-ness.” To Airlie this Carolingian-ness was a necessary condition for becoming king, but it did not in and of itself guarantee a throne. It is only the combination of Carolingian-ness and aristocratic support, which activates that Carolingian identity, that could secure a throne.5 It is the difference in aristocratic support, I think, that explains why Arnulf did not become king in 879 while succeeding in 887. In 879 it was, presumably, restricted mostly to some Carinthian and Bavarian supporters, but the pressures on the elite in 887 may have gave Arnulf additional leverage to gain their help in overthrowing Charles the Fat. Even still, it was by no means a peaceful transition. Arnulf appeared with an army of “Bavarians and Slavs” at an assembly to force the issue, and ended up issuing a huge number of grants in the first years of his reign to strengthen his ties to the elite.6 Although his birth status may have been one factor, it was evidently not the decisive element. This would be true later in the middle ages as well, with one particularly famous Conqueror being an illegitimate son. Succession was complicated in the middle ages, and rarely follows the “rules” that modern historians and commentators want. This is because succession, like kingship itself, depended on elite support. Without it, legitimate or not, succession and ruling was difficult if not impossible. That things do not follow pre-determined paths is the best lesson we can learn from history. Life is messy, and the stories we tell about the past should reflect that.

https://gameofthrones.fandom.com/wiki/Legitimization. No, I have not watched the entire show so don’t come for me. ↩

Airlie, Making and Unmaking, pp. 102-109. M. Becher, “Arnulf von Kärnten – Name und Abstammung eines (illegitimen?) Karolingers,” in L. Uwe (ed.), Nomen et Fraternitas: Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag (Berlin, 2008), pp. 665-682 at pp. 666-667. ↩

See Heidecker, The Divorce of Lothar II, pp. 73-99. See also S. Joye, “Family Order and Kingship According to Hincmar,” in West and Stone (eds), Hincmar, pp. 190-210. ↩

Notker, Gesta Karoli, II, c. 14, p. 78: Hic enim solus ramusculus cum tenuissima Bennolini astula de fecundissima Hludowici radice sub singulari cacumine protectionis vestrę pullulascit; Notker, Erchanberti Breviarum Continuatio, R. Zingg (ed.), “Notker Balbulus als Fortsetzer des Erchanbert-Breviars, mit Edition,” Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 74 (2018): 53-88, edition at 77-88, quote at 84: qui adhuc vivit, et o utinam vivat, ne extinguatur lucerna magni Hludowici de domo domini!; See also Notker, Gesta Karoli, II, c. 12, p. 74. ↩

Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 880, p. 116. ↩

A topic worthy of its own post perhaps… ↩