Borges' Library of Babel and the Internet Age

I am away traveling this week, so I decided to write something a little different, hopefully you enjoy my writing (or rambling, take your pick). Earlier this year I read, for the first time, Jorge Luis Borges’ short story The Library of Babel and was struck by how relevant it felt to the modern internet age.

The “Library” is a seemingly infinite construct that contains books of every permutation of letters. In short, it contains everything that was or will be written. Naturally many of the books are junk, an entire volume of the letters M C V repeating, etc. The inmates of the construct, “librarians,” are at first unaware of the order or nature of the library, but when they discover it contains every possible work:

The first reaction was unbounded joy. All men felt themselves the possessors of an intact and secret treasure. There was no personal problem, no world problem, whose eloquent solution did not exist — somewhere in some hexagon. The universe was justified; the universe suddenly became congruent with the unlimited width and breadth of humankind’s hope.1

I find this short story incredibly helpful in thinking about knowledge, the internet, and people. A common sentiment one finds on the internet is that it contains “everything.” Like the people in Borge’s Library, the internet became a symbol of a new frontier of society, where the “everything-ness” of the internet would create a new world unbound by previous obstacles of information and communication. In some cases this was true. More than that was the simple assumption that if you expose someone to the truth, they will believe it, a questionable proposition at any point in time. The theory of the infinite internet also assumes that we can find whatever we want, whenever we want.

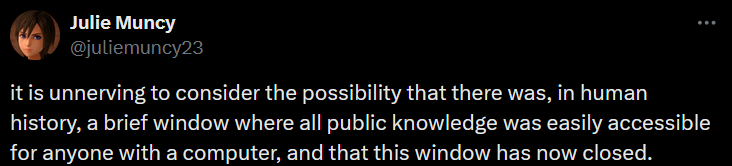

It is here where the people of the Library and the modern people of the internet overlap the most. Despite the Library containing every possible configuration of letters, there is no index or order of the books, meaning most of it is simply incoherent or pointless. As anyone who has recently had to use Google search, this is quickly becoming true of the internet, where the actual helpful information is washed away in a flood of garbage. Google’s prioritization of AI results accelerates this trend of being unable to access what a person is actually looking for. There is a distinction between knowledge existing, somewhere and knowledge being accessible. It does not matter if the knowledge exists if there is no way to get a hold of it. The people in the Library also realize this, and their “unbridled hopefulness was succeeded, naturally enough, by a similarly disproportionate depression.”2 Without an ability to search the giant fields of books, the people are driven to despair because they know somewhere in the Library is a book that would tell all the answers to everything, but they cannot reach it.

There is of course differences between the internet and the Library. Naturally, and despite claims to the contrary, the internet does not and never did contain the sum of all human knowledge. But there is something here in Borges’ words, the despair of knowing that the information is not accessible. As the internet becomes increasingly dominated by algorithms, we are losing the ability to search and find the things we want to. This is, perhaps, a more horrifying vision of the Library than Borges’ ever imagined, a Library where we never get access to all the knowledge not because we can’t find it, but because somewhere, something has decided it isn’t “what we want to see.” Trapped eternally in a prison of sameness, the algorithms decide for us. With an ever increasing share of the internet filled with junk, finding something spontaneously (a hallmark of the early internet) has become more difficult. We can see this reflected in how many do not venture outside the walled gardens of their algorithmically decided world. In my own experience teaching undergraduates, this can lead to frustrations when asked to find sources not on the internet or from reliable authors. There is a strong tendency to assume that the first, plausible sounding, Google result is “good enough” for use. The internet easily conceals the labor that goes into producing knowledge, and AI threatens this even more. Evaluating sources are difficult, and the algorithms provide an easy excuse to abandon that work. Would one be happier if all decisions would be made by an impersonal and hidden force? I recall here another short story by Borges, The Lottery of Babylon, where all decisions are made by lottery yet no one knows the mechanism or results of the lottery. Like one of Borges’ much-loved labyrinths, the internet continues to become denser and more imposing, offering few ways out. There is no Ariadne for this modern labyrinth but ourselves, in resisting the endless enshitiffication of the internet. Already the internet is dominated by corporations using us as the product, mining our data to sell to advertisers, worsening every available service in pursuit of higher margins.

Borges’ narrator, trapped within the Library, notes how each year the suicides become more common, to the point that he has gone long stretches of time without seeing another person. This makes him wonder: “I suspect that the human species…teeters at the verge of extinction, yet that the Library — enlightened, solitary, infinite, perfectly unmoving, armed with precious volumes, pointless, incorruptible, and secret — will endure.”3 To me that is the key element of Borges’ Library, that despite all the infinite knowledge contained within, it is fundamentally pointless. The internet too has the capability to disseminate vast knowledge, but only if it is designed to do so. As it currently trends, it is not meant to spread knowledge but content. Ephemeral, algorithmically and profit driven, pointless content. For one, I don’t want to be washed away on a sea of content. But for now we are all somewhat trapped within this construct, myself included (please subscribe). We can only hope that we find a way to lead us out of the labyrinth.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.