By Divine Grace We Were Placed in Front of Others

On the anniversary of Arnulf becoming king

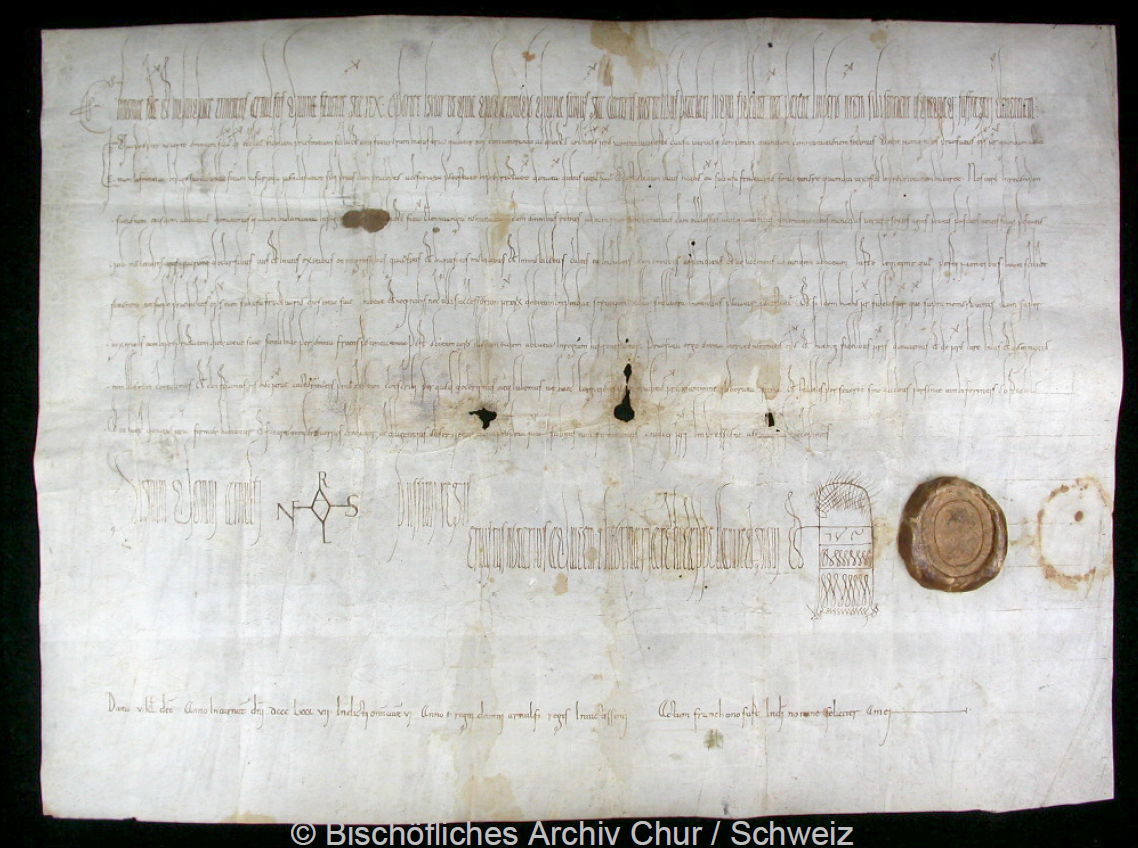

A bit of a shorter post this time, because of the holidays and trying to actually finish my dissertation. I did want to write something because November 27th is the 1,137th anniversary of Arnulf’s first charter as king. This charter came only ten days after the last charter issued by his uncle, Charles the Fat. The geography is also important: both charters were issued at the same place, Frankfurt. Regino, who was writing his chronicle in the early tenth century, would refer to Frankfurt as the principalem sedes orientalis regni or the “main seat of the eastern kingdom.”1 Charles the Fat had planned to hold an assembly of the great and the good before Arnulf interrupted and deposed him. This charter thus comes at a critical moment when it was necessary for Arnulf to demonstrate the credibility of his rule. We get some sense of this tension in the arenga of the charter. The arenga is often a phrase that connects the specifics of the individual grant to a broader outcome. For instance by giving to churches, the king secures their present prosperity and eternal salvation. As such they have been seen as fertile ground for arguments about kingship and authority. Arnulf’s first charter begins thus:

In the name of the holy and individual trinity. King Arnulf with divine grace favoring. Therefore it pleases us, that, because by a certain divine grace we were placed in front of other people, those who loyally obey our command, they wholly understand our clemency to favor them.2

Clearly, there is an argument here about the nature of Arnulf’s authority: God has chosen him to rule instead of other people. This phrase “we were placed in front of other people” was not particularly common in Carolingian diplomatics, but did have some precedents.3 The Latin is also doing something cute here because it literally surrounds the men (sibi/sentiant) with Arnulf’s authority (nostram clementiam): nostram sibi sentiant usquaque suffragari clementiam. This is something that is lost in the English translation, but in Latin stands out (to me at least).

Charters were often given in public ceremonies and especially at assemblies could be read out.4 The large single-sheet parchment and ornamented script had been partially designed to express the king’s majesty but also made them better suited for public display.5 One can imagine an amount of stage-managing here to emphasize Arnulf’s arrival and acceptance as king.6

This charter was an exchange between the king and Liutbert, the archbishop of Mainz. Liutbert was a highly political figure however. He had been the archchancellor for three successive kings: Louis the German, Louis the Younger, and Charles the Fat. His tenure as Charles’ archchancellor was quite rocky because he had been replaced by another bishop, Liutward of Vercelli, before regaining his position in late 887.7

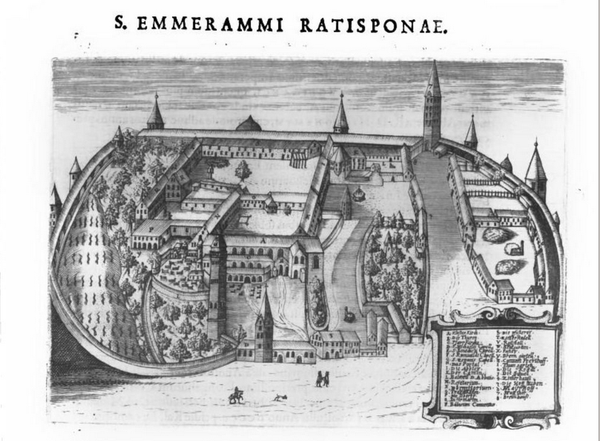

His quick acceptance of Arnulf’s kingship may have been a prominent signal to other elites that Arnulf was the real deal. Charles had even sent Liutbert to Arnulf as a last ditch effort to prevent the coup, so for Liutbert to publicly acknowledge Arnulf’s authority could have prompted others to acknowledge him. The Annales Fuldenses seems to suggest that Arnulf revoked offices, known as honores, from those who refused to support him.8 Charters may have operated as the proverbial carrot to the stick: support Arnulf and get rewarded, oppose and get punished. We find a huge surge in charter production beginning in 888, which coincides with Arnulf’s first assembly at the town of Regensburg where leaders from the various regions of the kingdom came to, presumably, acknowledge Arnulf as king. This is important to note: it seems that whatever happened at Frankfurt in November 887 was only the beginning of this process, but the assembly in 888 opened the flood gates. Arnulf granted a whopping 36 charters in just 888 alone, far more than any other East Frankish Carolingian king.9 Because these survive in different archives, and for many different recipients, I don’t think we can simply reduce this increase to how these charters survived. Instead I think it is far more likely that Arnulf really did grant substantially more charters in this period. Granting so many charters was smart politics: each recipient had to accept Arnulf’s rule as king and his centrality to the political order. At the same time, the more charters that Arnulf granted, the more pressure on other elites to fall in line lest they potentially lose out on royal patronage.

Some of these recipients were important figures under Charles the Fat, suggesting that this strategy was at least partially successful. By the end of 888 Arnulf had granted charters to almost every major institution in East Francia. It is hard to see this as anything other than a sort of full-court press to secure as much support as possible. In some cases the grants were also just a way of rewarding those who were loyal to the king. For instance Arnulf granted a charter in February 888 to a “soldier” (miles) named Engilger because of his support “before we accepted the name of king.”10 It isn’t entirely clear if Engilger had been important to the coup itself, or had somehow found himself in Arnulf’s service previously, but it is a very limited glimpse into the existence of Arnulf’s pre-existing political support before 887.

This is all to say that the coup in 887 was neither inevitable or spontaneous. It had its roots in Arnulf’s longer ambitions that stretched back to the 880s as well as the rapidly escalating succession crisis of Charles the Fat in 885-887. After the coup it was not a foregone conclusion that Arnulf would remain in power and the charters give us a sense of this unease. Arnulf was, seemingly, a smart political operator who understood the power of the charter. Each charter solidified his place as the center of the political order, depriving any potential resistance of oxygen. Granting the charters allowed Arnulf to rewire the political circuitry of the kingdom to now center only on him. It is easy for us to look back and piece together all these charters and narrative sources, but conditions on the ground in late 887 must have felt substantially more unstable. Would Charles stage a comeback? Would Arnulf also claim West Francia? Modern historians can say that the answers to both questions were no, but only in hindsight. Likewise the decline of the Carolingians was also not a definite ending. Even if the empire was broken up, and non-Carolingians had become kings, in 888, by 898 conditions looked more “normal” in that a Carolingian king ruled alone in both West and East Francia. This was a moment of intense political competition and innovation: it was not simply the Carolingian twilight.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.

Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 876, p. 111. ↩

D A 1: In nomine sanctae et individuae trinitatis. Arnulfus divina favente gratia rex. Oportet igitur, ut, quia quodammodo divina sumus gratia caeteris mortalibus praelati, hi qui fideliter nostro parent imperio, nostram sibi sentiant usquaque suffragari clementiam. ↩

It appears in two other charters of Arnulf DD A 19 and 85. It is almost identical to an arenga under Charles the Fat, DD CF 94-95, and 133. Originally it seems to be a modification of an arenga of Louis the German, see DD LG 96, 101-102, 107, 112, 115, 117, 122, 130, 139-140, and 164. It is also similar to two charters of Lothar I, DD LoI 61 and 92. See also D CF 99 and Formulae Imperiales e Curia Ludovici Pii, ed. K. Zeumer, MGH Formulae Merowingici et Karolini aevi (Hanover, 1886), no. 17, p. 298. ↩

This is usefully discussed in H. Keller, “The Privilege in the Public Interaction of the Exercise of Power: Forms of Symbolic Communication Beyond the Text,” in M. Mostert and P.S. Barnwell (eds), Medieval Legal Process: Physical, Spoken and Written Performance in the Middle Ages (Turnhout, 2011), pp. 75-108. ↩

There is a lot of literature here, but the best entry point, in my opinion, is H. Keller, “Zu den Sigeln der Karolinger und der Ottonen. Urkunden als “Hoheitszeichen” in der Kommunikation des Königs und seiner Getreuen,” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 32 (1998): 400-441. ↩

G. Althoff, “Colloquium familiare -- Colloquium secretum -- Colloquium publicum: Beratung im politischen Leben des früheren Mittelalters,” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 24 (1990): 145-167 and T. Reuter, “Assembly Politics in Western Europe from the Eighth Century to the Twelfth,” in P. Linehan and J. Nelson (eds), The Medieval World (London, 2001), pp. 432-450. ↩

Charles’ last charter is problematic but we can find Liutbert in a charter from September 887, D CF 167. ↩

AF (M), s.a. 887 ↩

For comparison Louis the German, Charles the Fat, Carloman, and Louis the Younger all granted ~5-7 charters. ↩

D A 17: priusquam regium nomen acciperemus. ↩