Chance Encounters of the Arnulf Kind

Webs of Connections in the Ninth Century

I am endlessly intrigued by historical coincidences, that is how various historical figures crossed paths before the events that they are known for. I find these crossed paths add a more human dimension to historical accounts that we don’t get when we reduce figures to representing historical trends. A person is not the outcome of history, they aren’t simply swept along any one path. Instead, the personal element is an underlying current, pushing and pulling people in different directions. These people had a history of their own that is often submerged from view. This problem is worse for the middle ages, where we may know nothing, or close to it, about a figure’s background. I’ve alluded to the personal animosity between Charles the Fat and Arnulf before as a motivation for the coup in 887, but where might this have come from? The normal view of Arnulf is one that places him on the periphery as a frontier commander largely left to his own devices but kept at arms length by his uncles in the 880s. But what if during this period Arnulf was making connections that would bear fruit later when he became king?

In November 882 we can find the emperor Charles the Fat traveling across the Alps from Italy and holding an assembly at the German city of Worms. There the great and the good of the realm came to meet with him before a campaign against the Vikings, who had caused a large swath of devastation in Lotharingia. The source, the Mainz continuation of the Annals of Fulda, tells us that at the assembly in Worms they agreed to a time and place for the armies to gather for the campaign.1 Our other continuation, the so-called Bavarian continuation, gives a similar report of Charles traveling to Worms and then gathering an army that proceeded to fight the Vikings at the Siege of Asselt.

It is this second continuation that provides an intriguing little detail: Arnulf leads the Bavarian part of the army as their “prince.”2 Did Arnulf show up with the army, or was he already at Worms? The Bavarian annalist reports that Charles returned from Italy because his brother, Louis the Younger, had died and he was to claim the kingdom. Louis had already absorbed Bavaria im 879/880, where he had left Arnulf in charge of the Carinthian and Pannonian frontier. It was the assembly at Worms that Charles received “the leading men from the kingdom of his brother.”3 The other continuation instead claims that Charles first traveled to Bavaria to receive the leading men, and then traveled on to Worms. We don’t have definitive proof of Arnulf’s appearance at the assembly, but we can argue that he was there. Arnulf was a not inconsequential figure, so he may have been one of the “leading men” who went to Charles. Indeed that he could be trusted with leading a contingent of the army signifies some level of trust by Charles. The leader of the Frankish army was Henry, perhaps the most accomplished and important military commander in the entire empire until his death in 886. The Bavarian annalist sets up Arnulf and Henry as the two non-royal representatives of Louis’ kingdom, now coming to Charles to assist against the Vikings. Perhaps it was Arnulf’s dislike of Charles’ conduct at the Siege of Asselt that led him to try to forge his own path in the Wilhelmer War the following year, or was in the back of his mind when he sought out the Vikings for battle at Leuven in 891.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.

Yet why would it matter if Arnulf was at the Worms assembly? First, Arnulf is often presented as a sort of peripheral military commander. He is over there in Carinthia. His presence at Worms would suggest instead that he was more involved in royal/imperial politics than we have evidence for. When Arnulf himself becomes king, he is adept at using assemblies and other tools of Carolingian government to rule, and I think he may have learned this under his father and uncles. That is, he doesn’t just show up out of nowhere with an army, he had already been involved in Carolingian politics for a while. It may also explain why Arnulf doesn’t seem terribly interested in reclaiming the entire empire; if he had watched his uncle have difficulties holding it together, Arnulf wouldn’t have wanted to repeat the same decisions.

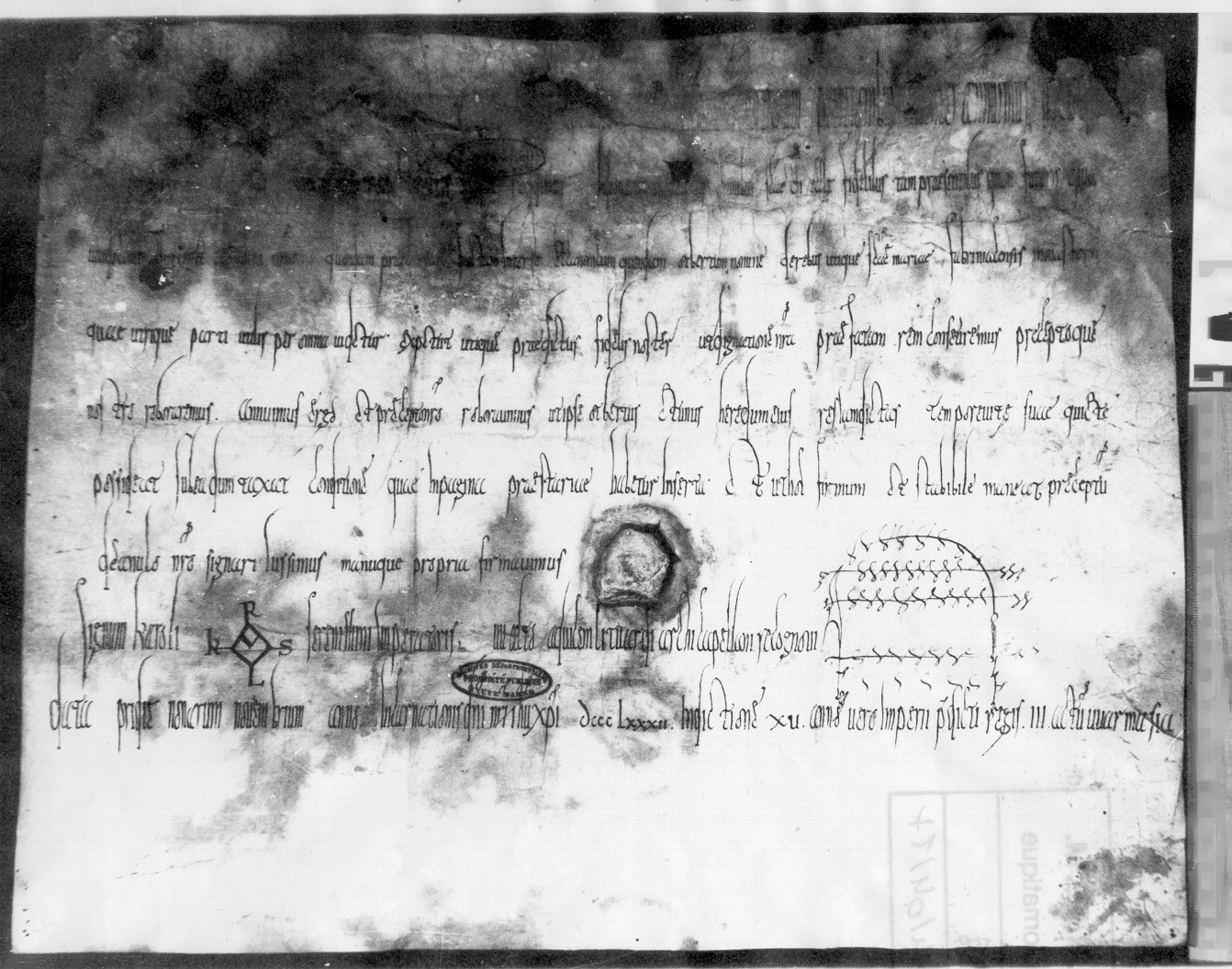

Second, there were a whole bunch of other people at this assembly. Several of whom would reappear during Arnulf’s reign. For instance Charles granted a charter for the dux of Spoleto Wido.4 Wido would have a lengthy career being a thorn in Charles’ side in Italy, before proclaiming himself king in 888 and becoming emperor in 891. Arnulf would actually fight several battles against Wido, and when he became emperor in 896 he required a new oath that prohibited giving assistance to Wido’s son Lambert II. Did Wido and Arnulf both see themselves as rivals after Charles?

In a bit of historical imagination we can envision the Worms assembly in 882 as a moment where Arnulf “arrived” on the political stage. His uncle Louis had died, leaving only Charles as an obstacle to his rulership. Also at this assembly was Charles’ cancellarius Waldo, who was the bishop of Freising. Waldo would show up a whole bunch during Arnulf’s reign and could even be described as Arnulf’s pastor bonus et rector optimus (“good shepherd and the best guide”).5 Perhaps Arnulf talked with Waldo about events in Bavaria, while being introduced to his brother Solomon, then a part of Charles’ entourage working as a notary. Solomon would become the bishop of Constance in 889 as well as Arnulf’s handpicked candidate for the abbacy of St. Gall. Solomon’s friend Hatto, who was also part of Charles’ following, could have been there too.6 Hatto was the future archbishop of Mainz and abbot of Reichenau and was described by a tenth century source as the “heart of the king [Arnulf].”7 Hatto may have also been a relative of Liutbert, the archbishop of Mainz until 889 who appeared at Worms in 882 as well.8 When Arnulf did stage his coup in 887, Liutbert was the one chosen as the negotiator between Arnulf and Charles. Liutbert had recently regained his position at Charles’ court, but was it also because Liutbert and Arnulf knew each other? In Arnulf’s first charter in November 887 it is none other than Liutbert who received the grant of the monastery of Ellwangen. Coming only a short while after Charles’ last charter, Liutbert is here presented as “[Arnulf’s] venerable and beloved archbishop.”9

Now I know, this is a whole bunch of names and connections, which is precisely the point! The highest levels of politics were a dense web, and Arnulf may have been able to find his way into the web at an event like the Worms assembly. The assembly at Worms in 882 was probably not the only run-in Arnulf had with these figures, but it provides an interesting example of a moment where we may be able to actually document some of these connections. Many, many figures from Charles’ reign show up in Arnulf’s court. Some of them are even explicitly noted as having served Arnulf before he became king. We often talk about historical actors in a somewhat abstract sense, doing things out of self-interest or to maximize their power, etc. where everything becomes boiled down to a “strategy.” What the chance encounters at the Worms assembly show is that this is not necessarily the full story. I alluded to personal dislike between Arnulf and Charles being a potential motivation for the revolt, but these meetings also provided an opportunity for forging positive connections. These were all people who knew each other, it was a small-ish political community. The forging of these political connections is badly documented because it is taking place behind the scenes at precisely these types of events.

Yet what this shows is we cannot discard the potential for the personal in historical activity. Historical figures, just like modern people, were not entirely rational actors but had a variety of motivations for their actions. It also helps us ground our analysis in the reality of lived people, who had dreams and fears like anyone else. Was Arnulf driven to become king because he felt slighted by his uncles? It is, sadly, a question without a good answer due to our sources, but this and questions like it should remain in the back of our minds. Arnulf did not become king because being a king is “better” than a count, etc. Instead, there was an entire backstory and motivation to the coup that is not just historical, but personal.

AF (M), s.a. 882, p. 98. ↩

AF (B), s.a. 882, p. 107: Baiowarii cum principe eorum Arnolfo. ↩

AF(B), s.a. 882, p. 107: receptis primoribus ex regno fratris sui. ↩

D CF 61. ↩

D A 170. ↩

See MacLean, Kingship, p. 172 citing the Liber Memorialis Romaricensis, E. Hlawitschka, K. Schmid, and G. Tellenbach (eds), MGH Libri Memoriales 1 (Hanover, 1970), fol. 9r, p. 15. ↩

Ekkehard, Casus Sancti Galli, c. 11, p. 148: cor regis. ↩

D CF 63. ↩

D A 1: venerando ac dilecto archiepiscopo nostro nomine Liutperto. ↩