Close Encounters of the Charter Kind: Munich Research Files, II

This week I have been in the Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv looking at charters in person. Not only has this been particularly useful academically, it is also just really cool to see them in real life instead of in a digitized copy. It is a remarkable accident of fate that we have so many originals (the actual single-sheet parchment) surviving from Arnulf's reign. With almost 100 of them, there are lots of opportunities to understand how they were produced.

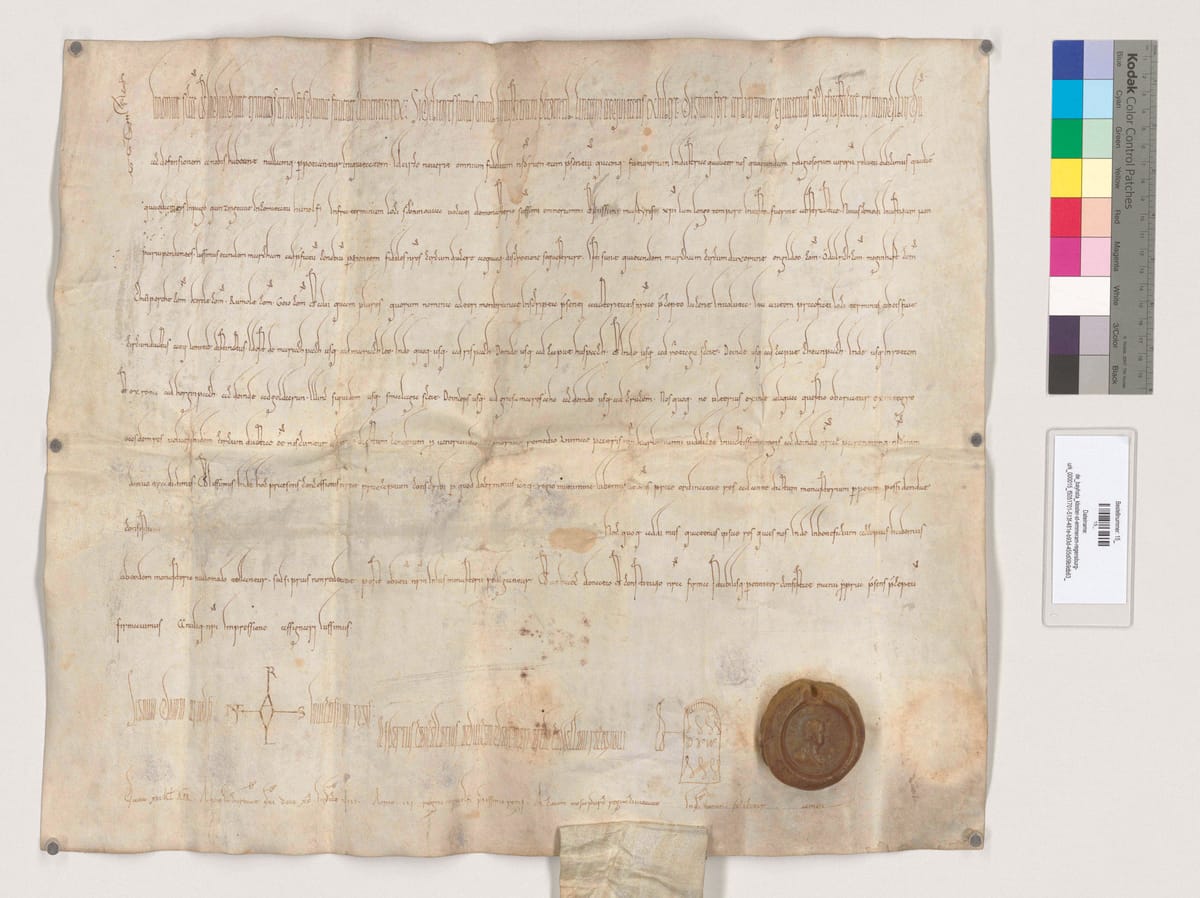

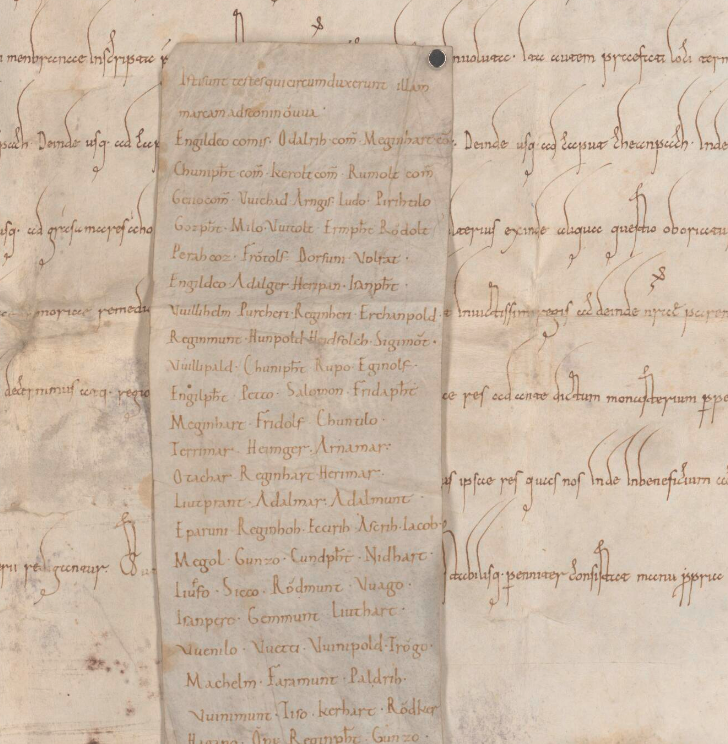

Take, for instance, the charter Arnulf granted for St. Emmeram, a monastery in Regensburg with important ties to the royal court.[1] Apparently the monastery had asked the king to help determine the boundaries of some lands in Schönau, largely the area between Munich and Passau. To do so, Arnulf had several counts walk the territory to determine the correct boundaries. When this was done Arnulf granted it to the monastery "for salvation of the soul of our father Carloman, of honored memory, namely the most unconquerable king."[2] Yet there are some oddities to this charter. Attached to the charter itself, BayHStA Kloster St. Emmeram Regensburg Urkunden 15, is a strip of parchment with a list of names, written in a standard book hand (that is, it is distinct from the charter itself). The list begins with an explanation of who these people were: "These are the witnesses who walked around that march at Schönau."[3] Some of the names on the list appear in the charter itself, but only those noted as counts. What I find extremely interesting is the fact that the charter indicates that the rest of the names "lie having been inscribed on another parchment [lit. membrane] folded on the present precept of our authority."[4]

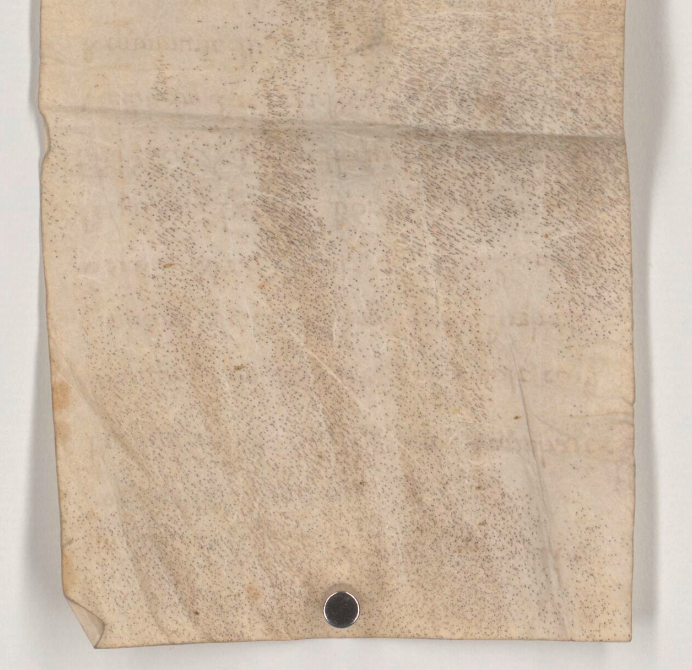

This raises some questions: was the charter or the strip of parchment written first? That the charter mentions the parchment strongly suggests that the strip already existed. I have a hunch that the strip of parchment represents the residue of the actual process itself, conducted in the field, and which includes the full list of witnesses. There are some reasons to believe that the strip of parchment wasn't intended for use in the charter: looking at the back of the parchment reveals it is still quite rough with many visible hairs left from the parchment making process. That is, this was not a deluxe piece of parchment, free from blemishes and created with the highest level of care.

Second, the shape of the parchment makes me think of medieval diptychs (writing tablets). Could this possibly have been written on wax and then transformed into a parchment equivalent? The use of the word inscribere is a bit strange, and the participle is extremely rare in 9th century charters. It appears in only three charters, two from Arnulf and one of Louis the German.[5] Technically, it can mean to write in, which recalls some of the language used about writing in wax tablets.[6] Or perhaps the strip of parchment was an off-cut from something else, and was pressed into service for this more administrative function.

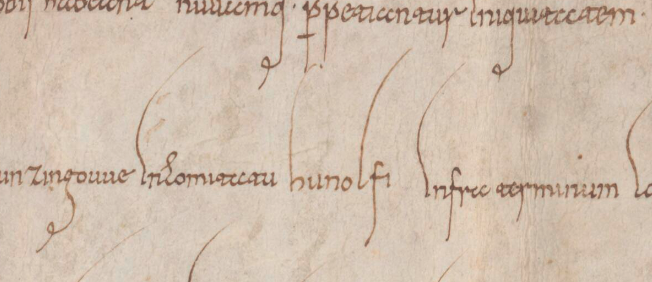

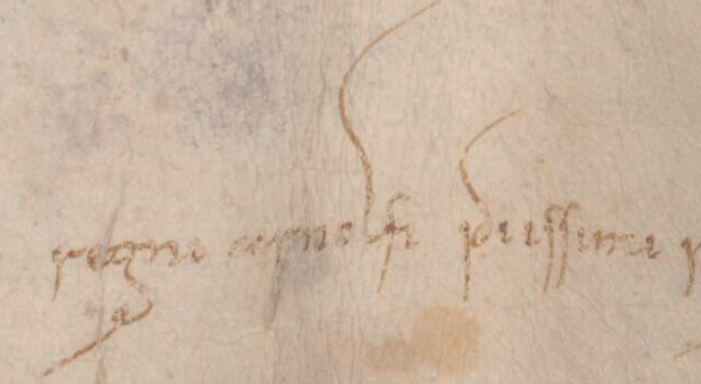

There are other clues for multiple stages of production. The lands lay in the region of count Hunolf, and in the charter we can see a gap in the manuscript where a different color ink has written in the name Hunolfi.

This hand, to me, bears similarities to the scribe that added the dating clause at the end of the charter. It is a bit hard to tell given the fading, and is easier to see in person.

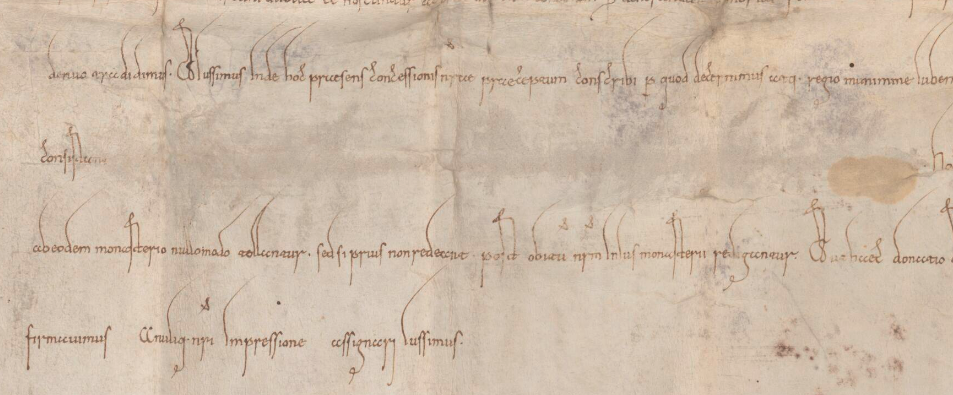

Taken together, we can suggest that the process may have looked like this: the king sent out his counts and men to survey the lands, at which point a record of the witnesses was taken. Then, the charter was drawn up, leaving a gap for the name to be filled in later (why? I am not entirely sure yet). Finally, the charter was brought to the court for final approval, at which point the dating clause and seal were added as well as the small strip of parchment.

The following charter, for Passau, seems to involve a similar process, but does not survive in the original. Intriguingly, we get a list of names here inserted in between last line of the charter and the dating clause. The names are not those who walked the boundaries, but the people who seem to be associated with the estates. It begins with a similar administrative phrasing: "and these are the names of the above written record."[7] Now, I don't know what the original looked like, so it is very possible that this was added in the original document. On the other hand, in the charters of Louis the German and Charles the Fat, names are generally inserted into the body of the text itself. Adding a list of names in between the body of the charter and the signum only takes place in one other charter for Arnulf, also involving the bishop of Passau Engilmar.[8] What these three charters suggest is perhaps a weird administrative practice, or something that was substantially more common and that we never see. Possibly under Louis the German and Charles the Fat these names were simply incorporated into the text.

None of this is clearcut evidence, but the surviving original gives us a clue into the process of negotiating and then creating a charter. One must assume that the recipient played a role here.[9] Frustratingly, the charter doesn't mention the abbot, Ambricho, who was also the bishop of Regensburg. Possibly, he was mentioned in the part of the charter that has been erased, likely in the 11th century when the monastery tried to assert its independence from the bishopric.[10]

Yet the description of St. Emmeram as "the most holy and pious" using the superlative suggests, perhaps, a recipient interest.[11] Further, the phrase, isti sunt testes, used to describe the witnesses, might give us a clue. Besides on this scrap of parchment, the phrase isti sunt testes does not appear in any other ninth century charter. It does appear, however, in private charters. Here the website dedicated to the formulae collections run out of the University of Hamburg is instrumentally helpful. Searching the phrase isti sunt testes shows that it was seemingly most common in private charters at Freising and St. Emmeram, but with differences in the ninth century, where it was more common at St. Emmeram (almost 40% of the documents versus 21% at Freising).[12] Drilling down further, almost all of the ninth century documents that use this phrase come in the years 883 to 899 (54 out of 63). Consider this a provisional argument, but this suggests to me that this reflects a St. Emmeram influence.

Needless to say, just from one charter we can gather a lot of information! I still have many more to see, with hopefully more insights to come! I hope this little walk through of a source was interesting, let me know if you have thoughts! Was this convincing? Am I completely wrong?

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can do your part in defeating the algorithm!

- D A 75.

- D A 75: pro venerandae memoriae remedio animae patris nostri Karlomanni videlicet invictissimi regis.

- D A 75: Isti sunt testes, qui circumduxerunt illam marcam ad Sconinǒuua.

- D A 75: quorum nomina alteri menbranae inscripta praesenti auctoritatis nostrae praecepto iacent involuta.

- DD A 75 and 158; D LG 116.

- On this see R.H. Rouse and M.A. Rouse, "The Vocabulary of Wax Tablets," Harvard Library Bulletin 1, no. 3 (1990): 12-19.

- D A 76: et hęc sunt nomina supra scriptę traditionis.

- D A 104.

- On this see M. Mersiowsky, "Towards a Reappraisal of Carolingian Sovereign Charters."

- See J. Lechner, "Zu den falschen Exemtionsprivilegien für St. Emmeram," Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche Geschichtskunde 25 (1900): 627-635.

- D A 75: sanctissimi emmerammi et piissimi.

- Freising (800-899): 182 out of 861 (~21%), (900-999): 187 out of 331 (~56%). St. Emmeram (800-899): 63 out of 161 (~39%), (900-999): 49 out of 90 (~54%). This was done by searching in the database there, so it may not be 100% accurate, so don't take these numbers as absolute gospel!