Why Do You Need to See the Manuscripts? Munich Research Files I

As some of you may know, I am spending two months at the Monumenta Germaniae Historica in Munich, Germany. In essence, I am interested in a seemingly boring question: who wrote Arnulf's charters? This isn't simply minutia, but is tied to long-standing debates about royal power and authority.

Much of the historiography revolves around two possibilities when it comes to charter production: first, that the king has a set of royal scribes (often described as a semi-bureaucratic "chancery") that writes them. Second, that the recipient of the document supplies their own scribe and produces it themselves. In cases where the king and his scribes exert a lot of control over the production of charters, meaning that most are written by them, scholars have seen this as evidence for strong royal authority. When, on the other hand, recipients produce more of the charters, this is viewed as a sign of weakening royal authority because the king and his court cannot impose their views on the recipients, but simply agree to what was put in front of them.

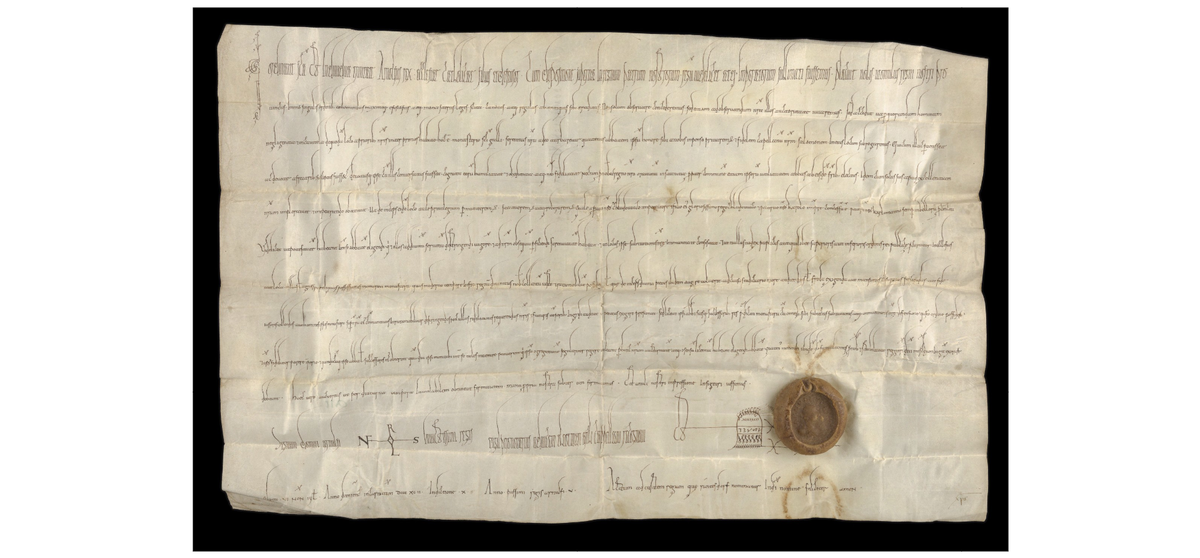

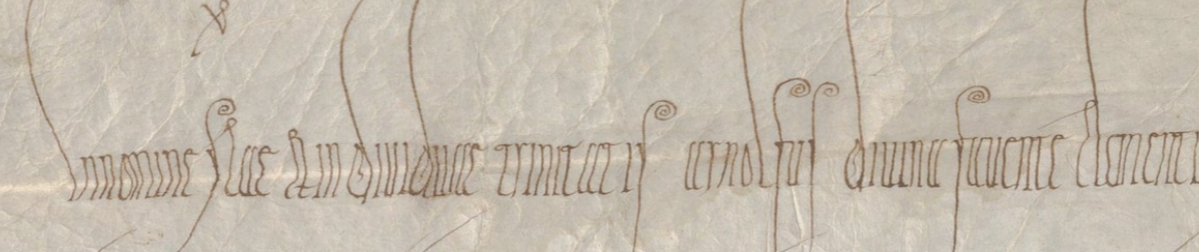

Recent work has really challenged almost all of this, however. In particular, the idea of a semi-bureaucratic chancery has been aggressively challenged, rightly, for not corresponding to actual practice and relying too much on the idea of the chancery as part of nascent state-building.[1] Likewise recipient production has also been reevaluated. In the context of papal charters. David D'Avray suggests that instead of revealing a lack of "state capacity", recipient production was a way to boost efficiency by offloading production from papal scribes.[2] This seriously complicates our attempts to use these documents. In short: whose ideas do they reflect, the court, the recipient, or both? There is a rich vein of scholarship on Carolingian charters that argues for their use as political communication by rulers, so this question matters quite a bit for how we understand them.[3] If they are produced by the recipient, how can they reflect a royal viewpoint? One potential way out of this problem is that charters often received royal oversight. We see this born out in Arnulf's charters, where a recipient scribe may write the "body" of the charter and then a court-scribe wrote the authenticating elements at the end including the monogram. This suggest some level of royal approval and consent to the language of the document. In Arnulf's charters we see a huge mixture of scribes working on charters, sometimes as many as three different scribes writing parts of one charter.

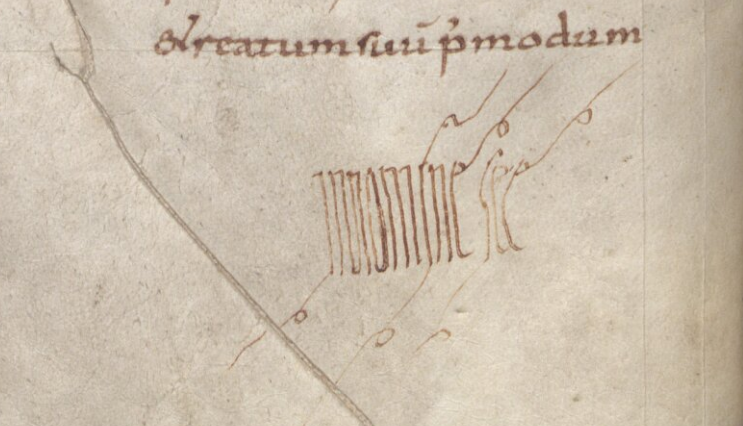

My time in Munich is primarily going to be spent on this question, based on a hunch I had while writing the dissertation. I noticed that several scribes seemed to be based in Regensburg. The editor of Arnulf's charters, Paul Kehr, identified several of these as specifically court scribes, but I am not convinced they make up a coherent "chancery" as much as they were somehow associated with the court as needed. What I want to look at is the charters themselves and compare them to other charters/manuscripts made in Regensburg towards the end of the ninth century. Can we identify them as Regensburg scribes? I am a bit skeptical that I will find anything close to a smoking gun, but we do have a late ninth century St. Emmeram manuscript where the scribe has added a word in diplomatic script in the margin, suggesting knowledge of these heightened diplomatic scripts. A similar example is found in Lyon, where pen-tests of diplomatic scripts reveal knowledge of these documents in non-chancery contexts.[4]

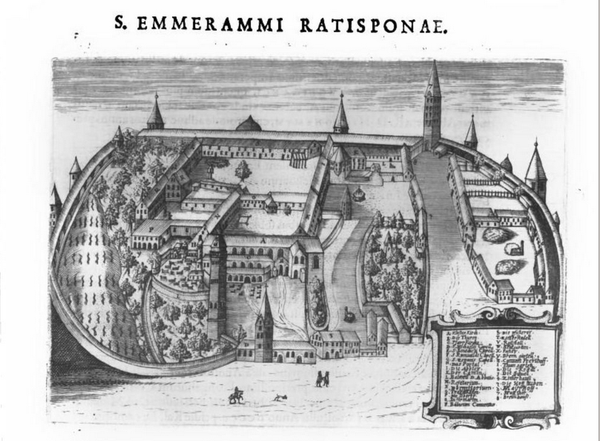

If it is true that some Regensburg scribes were associated with the court, it would also provide us a way out of the chancery/recipient dichotomy of production. Instead we would be able to speak of scribes, or more likely centers, with varying levels of association with the royal court.[5] Places such as St. Emmeram or St. Gall may have received more leeway, as it were, to produce documents because they were more tightly integrated with the court. Indeed St. Emmeram may have lent out scribes to the king as he traveled, as we can see in the case of a scribe known as Aspertus F, who leaves Regensburg in June 891 and produces charters while Arnulf was on campaign against the Vikings, returning to Regensburg in April of the next year.[6]

The 891 campaign gives us a tantalizing clue into how this loaning out may have worked. Further, Arnulf favored St. Emmeram as a center, giving it the Codex Aureus and the Arnulf-Ciborium as gifts.[7] In the 11th century an author would note how Arnulf chose "the blessed Emmeram as the defender of his life and kingdom” and that he was so devoted that he chose to build a “great palace” near the monastery of St. Emmeram.[8] Why not, then, take advantage of their scribes to produce charters for the king?

The first step in generating a new approach to understanding the charters is by understanding how they were produced. A collaborative process between court and recipient makes more sense given our knowledge of politics more generally, where consensus was highly valued. The charters could thus contain traces of royal ideology, recipient desires, and acceptance of these ideals by both parties. At the same time, however, the political context of each charter, and the exalted status of the ruler, means that the recipient was unlikely to be coming to the table as an equal partner.

For instance in 893 Arnulf granted a charter for the bishop of Toul, Arnald. Arnald evidently "neglecting the direction of our command, mixed himself with the company of another, who stole the rights of our kingdom, although for a short time."[9] Arnald came to Arnulf, according to the charter, to express his guilt over his actions and to beg forgiveness. It seems unlikely, at least to me, that this was really the outcome of a process of negotiation where both parties were operating with equal leverage. Instead, Arnald may have needed to accept a specific version of events that emphasized the futility of supporting a non-Carolingian ruler in opposition to Arnulf and which further expressed Arnulf's mercy and love for God by his returning the lands. The charters thus encapsulate a ton of information about relationships and power, alongside their performative and narrative elements. Without a better idea of how they came into being, it is harder to tease out what this process of negotiation may have looked like.

Unfortunately in the case of this charter we don't have a surviving original, so we can only work from the text itself. My goal is to combine this approach with the surviving originals to see if we can get any insights into this process of production and negotiation. Who knows what I will find, stay tuned!

I will do my best to write while in Munich, but it may be shorter or have to wait until my return, depending on how much time I have.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can do your part in defeating the algorithm!

- The key work is probably Mark Mersiowsky, "Towards a Reappraisal of Carolingian Sovereign Charters" in Karl Heidecker (ed.), Charters and the Use of the Written Word in Medieval Society (Turnhout, 2000). See also Wolfgang Huschner, Transalpine Kommunikation im Mittelalter: diplomatische, kulturelle und politische Wechselwirkungen zwischen Italien und dem nordalpinen Reich (9.-11. Jahrhundert) (Hannover, 2003) but with the criticisms in Hartmut Hoffman, "Notare, Kanzler und Bischöfe am ottonischen Hof," Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 61, no. 2 (2005): 435-480. For a good modern overview of the debate in the Ottonian world see Levi Roach, "The "Chancery" of Otto I Revisited," Deutsches Archiv für Erforschung des Mittelalters 78, no. 1 (2022): 1-74.

- David d'Avray, The Power of Protocol: Diplomatics and the Dynamics of Papal Government, c. 400-c.1600 (Cambridge, 2023).

- I won't cite it all here, but there is a lot. Some examples include Elina Screen, "The importance of the emperor: Lothar I and the Frankish civil war, 840–843," Early Medieval Europe 12, no. 1 (2003): 25-51. Geoffrey Koziol's two books are particularly informative in casting charters as "performatives", Begging Pardon and The Politics of Memory. Recently, Jon Tickle has taken this up in the case of English charters in "‘Corpora gloriosorum regum’: Conflict, Memory and Performativity in a Charter from the Reign of King Æthelstan," Journal of Medieval History 51, no. 3 (2025): 348-367.

- From the really fascinating article by Michele Baitieri, "Diplomatic Script and Pen Trials: The Case of Carolingian Lyon," Scrineum Rivista 21, no. 2 (2024): 201-240.

- This is not unprecedented, St. Denis was the main producer of recipient copies under Louis the Pious and Charles the Bald, see Mark Mersiowsky, "Graphische Symbole in den Urkunden Ludwigs des Frommen," in Peter Rück (ed.), Graphische Symbole in mittelalterlichen Urkunden. Beiträge zur diplomatischen Semiotik (Sigmaringen, 1996), p. 340.

- DD A 90, 92, 93, 95, and 100.

- There is some debate over the date of the ciborium, I defer to Wolfram, Arnulf von Kärnten: eine biographische Skizze (Ostfildern, 2024), pp. 109-110.

- Arnold, De miraculis beati Emmerami, MGH SS 4, p. 551: Is namque sperans, Deum sibi sic fore propitium, elegit beatum Emmerammum vitae suae ac regno patronum, adeoque illi adhesit, ut in vicinitate monasterii regio cultui aptum construeret grande palatium. The archaeology bears out that there was a connection between palace and monastery.

- D A 112: postposito nostre dominationis regimine, alterius se immiscuit societati, qui regni nostri iura, modico quamvis intervallo, subripuit.