Historians at Work

Let's get technical

Have you ever wondered how history is made? By this I mean how historians go from the raw materials (the sources) and produce what you see in a textbook or wikipedia page. It is a pretty common perception that there is a unbiased true history that historians are meant to uncover. Yet as Borges writes, “Reality is precise, memory is not.” What Borges is hinting at is that there is an objective reality that occurs, but our recollection of that reality is often imperfect. Historians work with the artifacts of the historical past, both textual and physical. They do not tell a straightforward story and are often frustratingly vague about what we want to know. What historians do is take these disparate pieces of information and interpret them. Bias, or an interpretive model, does not mean a given account is inaccurate. These are problems inherent to any historical interpretation, even supposedly “objective” accounts. Really what it means is that the historian looked at the evidence from a certain viewpoint, frankly a necessity if you want to get something that isn’t 900 pages long. To evaluate scholarship means looking at how historians use sources: are they pushing it beyond what the source says? Are they looking for a source to support an argument, and not the other way around? Good historical scholarship proceeds from sources. This is, I might gently suggest, a pretty good way of interpreting any argument.

I didn’t begin my dissertation by thinking that Arnulf was considered a Carolingian by contemporaries. Instead, I asked the question: how did contemporaries understand Arnulf’s place in the dynasty? Yet there are also tons of smaller details and investigations that take place largely hidden from view. The small details and decisions are then built up into a larger argument. I want to look at one of these small details that came up while working on a chapter for my dissertation, that highlights how even small claims require sustained attention. What follows is a “forensic” account of how I go from a document to my interpretation of it, with all the bits and bobs that will not appear in the finished product. I am intentionally picking a rather mundane example here so you can see how historians need to interpret the evidence even for something “apolitical.”

For this chapter I was working on a charter granted by Arnulf on August 7th, 897. Charters are documents that are records of land grants and privileges (usually). Charters are broken down into two main types: private/local and royal. This charter was written in the king’s name, which makes it particularly useful for seeing potential royal ideas. They are not exactly straightforward documents and it is easy to get lost in them. This charter was granted to “St. Cyriacus the martyr of Christ.”1 Perhaps confusingly, this is a place, not a person. So where is this place? The charter itself does not say specifically, but we can infer that it is located in Worms based on textual information in the charter. The person asking for the grant is Thietlach, the bishop of Worms, and the servants Arnulf granted are located in “the city of Worms.”2 Later in the charter it notes that the saint’s body lies in “the place Niuuihusa.”3 You all know where Niuuihusa is right? If we were looking at the charter in the original (the actual parchment sheet) we would be pretty lost here without a very, very good sense of medieval place names. Luckily there are a couple online resources. First, is the Orbis Latinus which produces no results if we search “Niuuihusa.” Similarly the Geschichtliche Ortslexikon Deutschlands (GOLD) returns no results if we search that either. Medieval scribes occasionally used two u’s as a ‘w’ (which makes sense, when you think about it) so I tried searching “Niwihusa” and sure enough we get a hit in GOLD for Neuhausen, near Worms. If you google search Niwihusa directly, you get taken directly to the German wikipedia page for Neuhuasen, which notes the monastery of St. Cyriacus there. German wikipedia is pretty great for finding place names, because they frequently give the medieval/Latin names.

Great, all that work to discover the location of the place in the charter: the monastery of St. Cyriacus in Neuhausen which is a borough of Worms. The next thing I wondered, given that it was noting the saint himself, was whether this might mean anything. Was Arnulf granting this charter because St. Cyriacus had some sort of medieval resonance? A connection to the court? So first I headed off to the Wikipedia page to get myself oriented before going deeper if something seemed relevant. Cyriacus being a Roman martyr piques my curiosity, because Arnulf grants other charters to institutions dedicated to Roman martyrs in this period. At one point in the chapter I had a section called “Arnulf’s Roman Martyrs” but I had to largely scrap it because I needed the space for other things. The obvious reason Arnulf might be more interested in these Roman figures is because he had just traveled to Rome in 896 and been crowned emperor. Not only had he become emperor, he brought relics back with him from Rome. Celebrating Roman martyrs may have been a way of further emphasizing Arnulf bringing the imperial title north of the Alps.

More than that however, is the feast day associated with Cyriacus: August 8th. If you recall, the charter was granted on August 7th, the day before his feast day. A strange coincidence, but maybe the date for the feast in the early Middle Ages was different that it is in the modern day. So how would we know when a feast day was in 897? Well we can look at a source called a martyrology, which helpfully lists brief biographies and dates for different saints.

Well hold up, I can hear some of you say, how can you tell it was what people in this time and place believed?

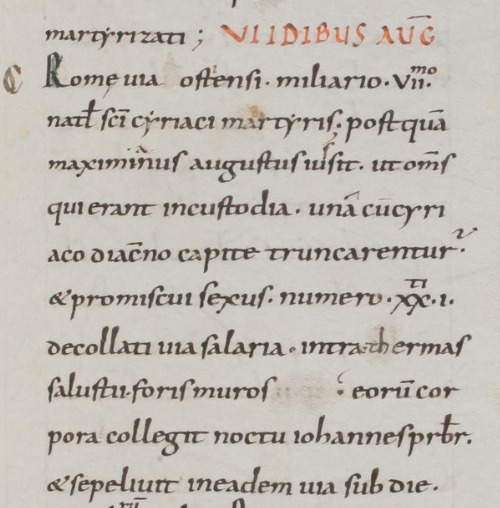

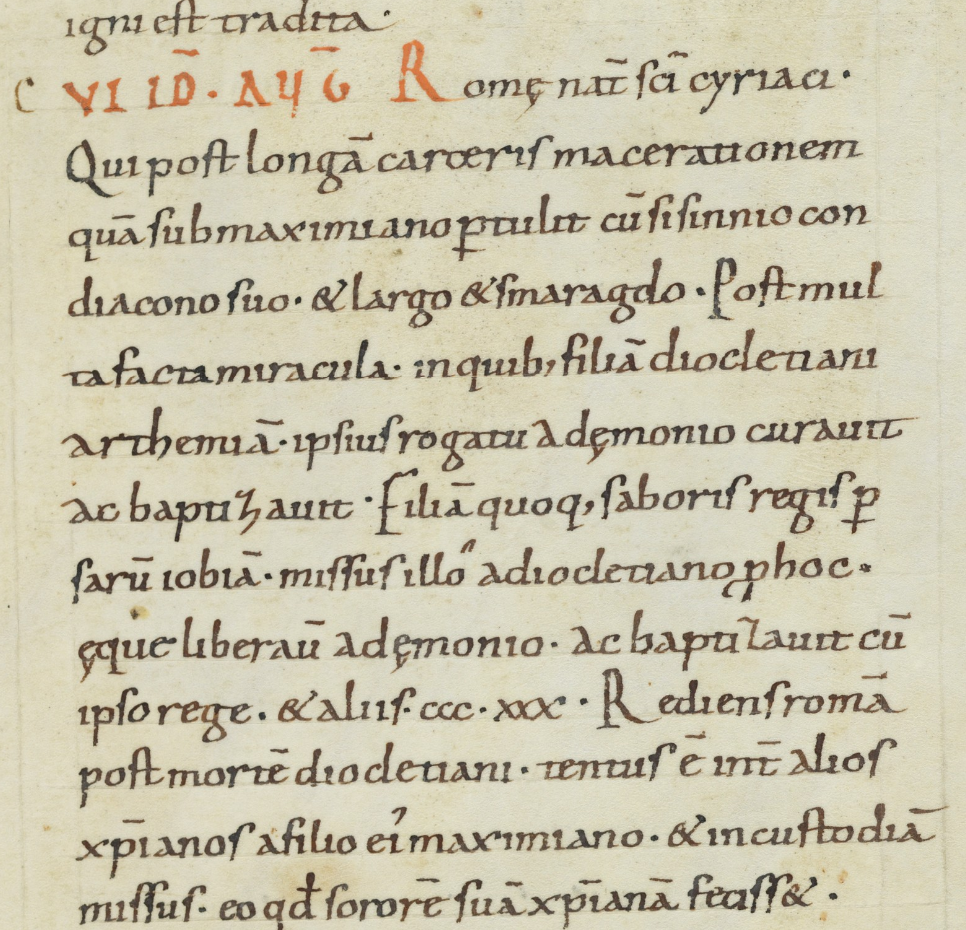

Fortunately, we have two martyrologies that we can trace not only to this period, but to the region as well. The first was written by the bishop of Vienne Ado in the mid-ninth century, but a copy survives at the monastery of St. Gall from the years 880-890. Helpfully for us, the manuscript has been digitized so we can go look at it directly. As I mentioned in an earlier post, each manuscript has its own story to tell, even if the text as it appears in a printed edition differs. For our copy of Ado, we need to find the corresponding entry for August 8th and see if our saint Cyriacus appears there. Of course, the scribes would not write “August 8th” so we need to convert that into the format they would use: VI Idibus Augustus. Sure enough we can find Cyriacus under that date in the martyrology.

We can repeat the process with another martyrology from St. Gall, this one written by Notker the Stammerer. Our copy of Notker was likely written around 900, making it pretty much current to Arnulf’s 897 charter.

All this to say, that the evidence suggests that St. Cyriacus’ feast was on August 8th in the early Middle Ages and this date was known to be his feast in Arnulf’s kingdom. We would be on shakier ground, perhaps, if these manuscripts both came from England or somewhere further afield, but these are within Arnulf’s realm. Ok so why care that the charter was granted on August 7th and the feast is August 8th? We can’t say for sure that the charter was meant to coincide with the feast day, and it is odd that is the day before and not the day itself. It does suggest that Arnulf wanted to grant the charter close to the feast day, perhaps as a way of celebrating the saint through the grant. Kehr, the editor, in laconic fashion notes that when the scribe wrote the document the “current day” was appended to the charter. It is one of the few that doesn’t have an accessible digitized version so I cannot tell for sure what Kehr means. However it sure sounds like there was a blank space left for the scribe to add the date later, and did so when the charter was granted. However the charters from Worms can display some tinkering from later scribes, so we need to be extra careful with this one. In the end, all of this work is for a relatively minor point in the chapter, which itself forms part of the bigger work. This is how all of this work looks in the context of the chapter:

Arnulf granted two further charters on August 7th, 897 at Frankfurt that dealt with St. Cyriacus, located within the city, and the episcopal church. Granted the day before the feast of St. Cyriacus, these the grants may have been issued to coincide with the feast day.

So in the end most of this work is relatively “pointless” because there is no smoking gun here. There is no easy answer or clear connection. Instead, despite all the spade work, the end result is largely a “maybe this is connected, but I wouldn’t bet my life on it.” Just to get to this point, however, required traveling through multiple sources and manuscripts. Now, imagine a similar process playing out over ~300 pages and you can get a sense of how much work goes into historical research. Indeed in this case it actually made it into the text, in many other cases it does not even make the cut. Historians are not simply looking at a source and typing away, despite what some may think. Of course, there are plenty of shortcuts I used to do this, I already knew that Ado and Notker can be used for investigating a feast day, and the editor of the charter tells me where the monastery was.

My point, however, is what looks like a baldly stated “fact” actually requires multiple levels of interpretation. What we often mean by “bias” is that an account has a specific perspective or argument. These can be submerged, or obvious, but no historical account is free from the fact that it is making an argument about the past. Even the most “objective” account has an intellectual framework supporting the argument. The real criteria is not objective/subjective, but how carefully someone is paying attention to context and detail. For those who are not historians, this is probably a process that is completely concealed from view if you read a work of history. That is, when you open a book and it says that X person did Y thing on Z date, there is an entire process of thought and interpretation behind that claim. That does not mean, however, that it is “biased” and therefore unreliable. One could argue that I am “biased” because I am a political historian, meaning I am interested in questions of politics. I don’t look at the sources for what they can tell us about religion, for instance, at least that is not my main goal. I look at the sources with a specific question in mind, and then build the argument from the evidence.

Historians use context, and their expertise, to create coherent narratives from the evidence we have left. This is a particularly difficult task for medieval historians, where the evidence might be patchy and uneven. But this does not mean that we cannot know anything about the past, instead historians have found increasingly clever ways at getting at the things we want to know about: from rural village life, to aristocratic women, to industrial production after the fall of the Roman Empire. There is no “pure” history handed down from the heavens to the historian, that isn’t how it works. Instead, history is crafted, interpreted, and presented.