How often did the king go to Mass?

Some thoughts, an incomplete investigation

While at dinner with a friend of mine the other night he asked me a seemingly simple question that I had never thought about before: how frequently did the king go to Mass? I am not, primarily, a religious historian so this had never really crossed my mind. I knew surely they went to Mass, but I had never actually looked into it myself, and I definitely had never considered how frequently a king (or anyone really) would go to Mass in the Early Middle Ages. Since I hadn’t come up with something to write for this week’s post, I decided to try to figure out the answer to this question as a sort of “watch me work through the process of learning something.” Note: I am not making any promises this is the definitive answer here so don’t take it as such! What I did was primarily look through things I had direct access to without having to trek off to the library since I am deep in dissertation writing mode and physically don’t have enough bookshelves to store any more books! I am sure you could add much more to the picture I am going to sketch out here, take this more as an outline than a full guide.

The first thing I did was search the Annals of Fulda for mentions of “Mass” and was quickly disappointed. Only two relevant passages describe a king attending Mass, and both involved Arnulf preparing for battle in Italy, in 894 and then in 896.1 That was a bit odd to me, why would both mentions involve Arnulf and battle? My hunch is that the annalist wanted to emphasize Arnulf’s concern about the battles, and by mentioning the Mass it reiterated divine support for Arnulf’s victories. He was a good Christian king, as they say.

Either way, attending Mass on the battlefield was probably not the norm, so the annalist may have also been noting it precisely because it was unusual. I wanted something more mundane. When the king was at his palace did he go to Mass every day? My next stop was the Annals of St-Bertin, which in the later sections were likely written by the archbishop of Reims Hincmar. A sort of prickly fellow who was very interested in matters of church and politics, I figured if anyone was gonna mention kings going to Mass, it would probably be him.2 Sure enough, we find substantially more mentions here. Yet like the Annals of Fulda, none of the examples are particularly mundane. We have an episode in 849 where Charles the Bald’s young son climbs the ambo of the church and declares that he wants to renounce the secular world.3 The bishops evidently obliged and tonsured him on the spot! A similar event is the account of the 873 assembly where the young Charles the Fat stands up and declares his renunciation of the secular world.4 Accounts differed on Charles’ actions here, and the Annals of St-Bertin claim he was in fact possessed by a demon.

Needless to say, these aren’t exactly your average Masses (well I hope not, don’t know what kind of churches you are going to). Part of why we have these included in the narratives is because they were shocking and disruptive. As Neil (Robert Pattinson) remarks in Tenet (2020): “No one cares about the bomb that didn’t go off, only the one that did.” It is a common historical conundrum that our evidence for events often only appears when things are unusual in some way. People rarely feel the need to explain or remark upon the ordinary. We all do this, do you mention a boring commute, or only a commute when something bizarre happens on the way?

Yet I still wanted to know the answer so I turned next to a source I hoped would have more to say: Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne. This is, of course, a pretty well known source precisely because it claims to give us details about Charlemagne himself from someone who knew him personally. Einhard was also trying to make Charlemagne look good, so we can’t just plainly accept him at his word. Einhard, after all, was responsible for generations believing that Charlemagne really did not want to be crowned emperor; a pretty implausible conclusion! It is Einhard, at last, who gives us a clue to go on: “As far as his health permitted, he went eagerly to church morning and evening, and also for night prayers and for Mass.”5

A later biographer of Charlemagne, Notker, also notes the king attending Mass.6 Notker also suggests that Charlemagne may have gone to Mass every day, at least during Lent: “Charles, who was profoundly religious and temperate, had this custom: during Lent he would take food at the eighth hour of the day, after he had completed the celebration of Mass along with Vespers.”7 In another passage Notker mentions that “Charles used to go at night to Lauds” and that when the hymns were finished Charlemagne would then “put on his imperial garb for a while.” Meanwhile the courtiers, apparently waiting for Charlemagne “would come to that predawn Office and wait watchfully for the emperor either in the church or in the porticus…as he was going to the solemnities of the Mass.”8 It is also worth thinking about that Notker was writing almost 60 years after Charlemagne’s death. The portrait of rulership in his history may be meant to serve as a model of what a good king should do versus a simple reflection of what Charlemagne did.9 That Notker is emphasizing the king attending Mass suggests that this was something contemporaries in the 880s valued as well.

There is other evidence that attending Mass seems to have been a regular activity for the ruler: when Charlemagne died in 814 and the news was brought to Louis the Pious a courtier who had “his custom to see his lord in the morning” urged Louis that “Let us all rise and hurry to the dear church, for the time has come to sing our vows to God.” Our source, Ermoldus Nigellus, claims that “when day arrived, Masses were sung.”10

This is all, of course, pretty vague on details. What does stand out, at least, is that these sources all suggest that the king attended Mass pretty regularly. For my purposes that is a good enough answer because I don’t need to know precisely how often the king went.11 There always comes a point in research where the historian needs to move on, lest they become permanently lost in the forest.

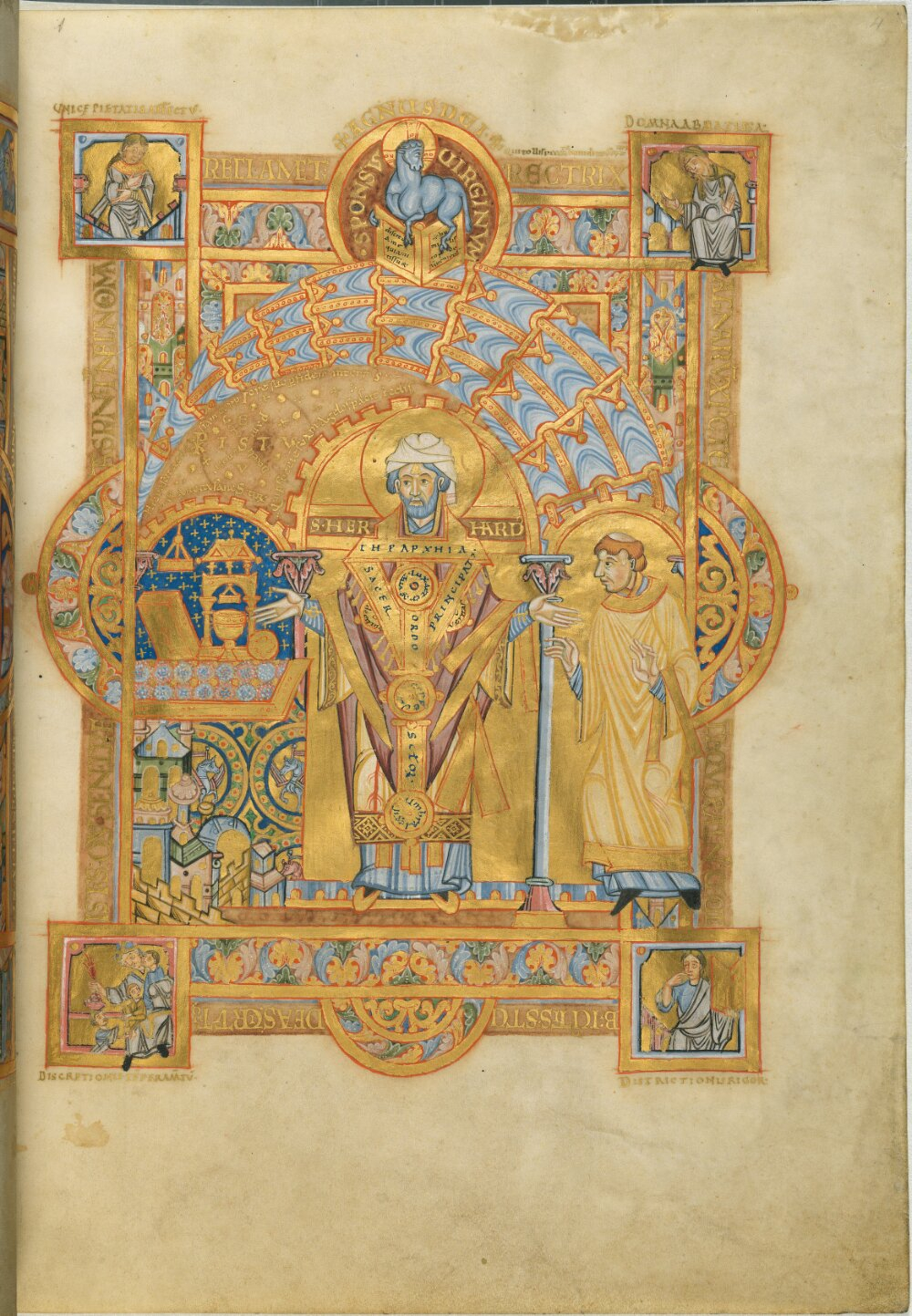

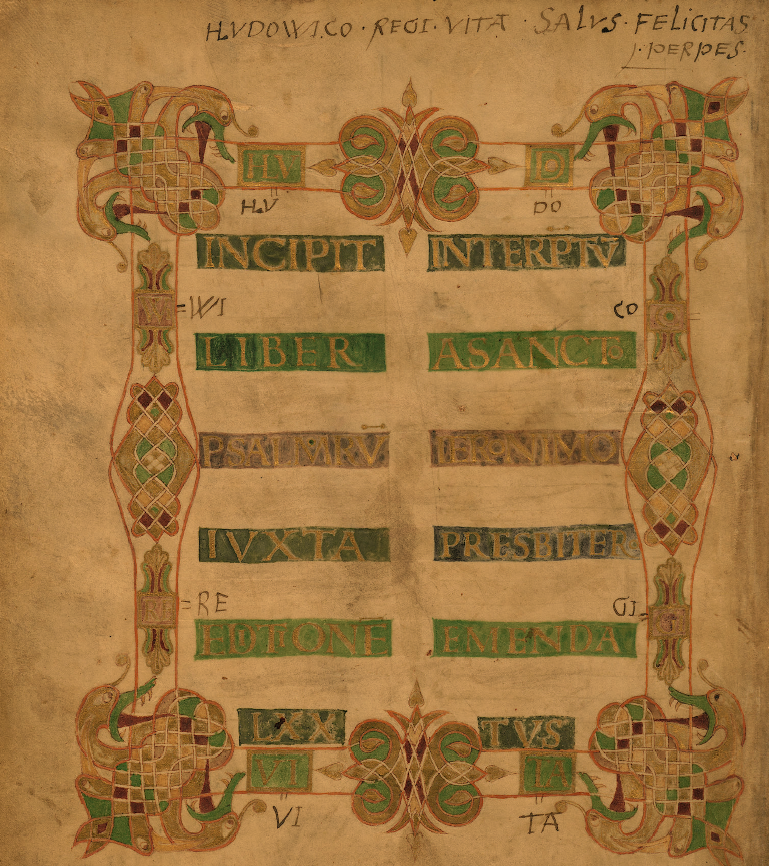

One thing I have not answered yet is how kings themselves felt about any of this. All of the information above is from the perspective of outsiders watching the king. It is easy, and common, to dismiss royal interest in religion as a veneer for a sort of cynical political mastermind. Yet our evidence seems to indicate that kings really did take this seriously. There are numerous instances of kings seeming interested in ensuring correct religious practice, and accusations of improper behavior could be a dangerous threat against rulers.12 For instance the psalter of Louis the German survives and is now kept in the Berlin State Library.

We also know that these books could enjoy a long life: at a later date someone added a short prayer to the Ludwigspsalter called “A Prayer to be Said Before the Cross” with an accompanying image of a man kneeling before the Crucifixion. I won’t give the game away here on the identity of the man, but there will be a post at some point on this prayer and the image. Needless to say, adding a prayer to the end of the psalter suggests that the book was continuing to be used well after its original date of production. More than that, kings regularly requested, and received, works of Biblical exegesis. Raban Maurus, the archbishop of Mainz, wrote a commentary on the Book of Daniel and sent it to Louis the German.13 Of course, kings often acted in ways contrary to what we might expect a “good Christian” to do. But kings took their spiritual responsibilities seriously, and believed in it. More than that, others believed in the king’s role within a political order that emphasized his divine sanction.14 It is easy to dismiss all of this, and people often do, as simply a veneer covering a brutal and oppressive regime. That is, I think, too simplistic an approach to understanding not just medieval rulers, but medieval religion. We do not need to agree with medieval people, but we also don’t need to see them as weak-minded simpletons.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work.

AF (B), s.a. 894, p. 123; AF (B), s.a. 896, p. 127. ↩

There is a lot written on Hincmar, a good starting point is: C. West and R. Stone (eds), Hincmar of Rheims: Life and Work (Manchester, 2015). ↩

AB, s.a. 849, p. 58. ↩

AB, s.a. 873, pp. 190-192. This is reported in the Annales Fuldenses as well. On this event see S. MacLean, “Ritual, Misunderstanding, and the Contest for Meaning: Representations of the Disrupted Royal Assembly at Frankfurt (873),” in B. Weiler and S. MacLean (eds), Representations of Power in Medieval Germany, 800-1500 (Turnhout, 2006), pp. 97-119 and J. Nelson, “A Tale of Two Princes: Politics, Text and Ideology in a Carolingian Annal,” Studies in Medieval and Renaissance History 20 (1988): 103-141. ↩

Einhard, Life of Charlemagne, trans. T. Noble, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious: Lives by Einhard, Notker, Ermoldus, Thegan, and the Astronomer (Penn State University Press, 2009), c. 26, p. 43. ↩

Notker, Deeds of Emperor Charles, trans. Noble, I.8, p. 65. ↩

Notker, Deeds of Emperor Charles, trans. Noble, I.11, p. 68. ↩

Notker, Deeds of Emperor Charles, trans. Noble, I.31, p. 86. ↩

Notker was writing for Charles the Fat, see S. MacLean, Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire (Cambridge, 2006), pp. 199-229. ↩

Ermoldus Nigellus, In Honor of Louis, trans. Noble, Book 2, p. 145. ↩

If I had more time, or it was a critical issue for interpreting a piece of evidence, I would have to go digging a bit deeper. Unfortunately, I have a chapter to finish. ↩

See M. de Jong, The Penitential State: Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814-840 (Cambridge, 2009) and S. Patzold, Episcopus: Wissen über Bischöfe im Frankenreich des späten 8. bis frühen 10. Jahrhunderts (Ostfildern, 2008), esp. pp. 135-168. ↩

It is mentioned in MGH Epp. 5, no. 34, pp. 467-469. A ninth or tenth century copy survives, Karlsruhe Badisches Landesbibliothek Cod. Aug. perg. 208, fol. 3v which mentions a “most noble king Louis” (rex nobilissime hludouuice), accessible here: https://digital.blb-karlsruhe.de/blbhs/content/titleinfo/3294902. ↩

This has a massive literature, here are some things I’ve found useful: Y. Hen, “The Christianisation of Kingship,” in M. Becher and J. Jarnut (eds), Der Dynastiewechsel von 751: Vorgeschichte, Legitimationsstrategien und Erinnerung (Münster, 2004), pp. 163-177; M. de Jong, “The Empire as ecclesia: Hrabanus Maurus and Biblical historia for Rulers,” in Y. Hen and M. Innes (eds), The Uses of the Past in the Early Middle Ages (Cambridge, 2000), pp. 191-226; G. Heydemann and W. Pohl, “The Rhetoric of Election: 1 Peter 2.9 and the Franks,” in R. Meens, D. van Espelo, B. van den Hoven van Genderen, J. Raaijmakers, I. van Renswoude and C. van Rhijn (eds), Religious Franks: Religion and Power in the Frankish Kingdoms: Studies in Honour of Mayke de Jong (Manchester, 2016), pp. 13-31; G. Heydemann, “The People of God and the Law: Biblical Models in Carolingian Legislation,” Speculum 95, no. 1 (2020): 89-131. ↩