Keeping it in the Family

What is the meaning of Arnulf's weird name?

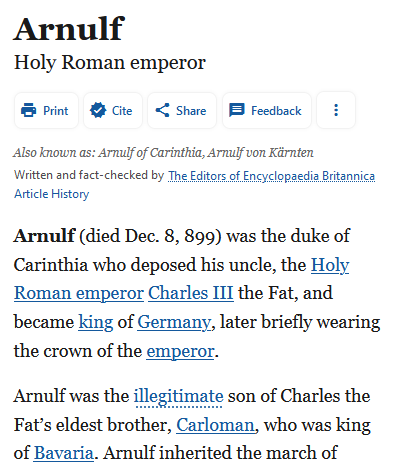

Anyone who has browsed through a list of medieval kings would come away with the impression that a lot of them were named Charles, Louis, or maybe Henry. A look at the Carolingians of the ninth century would reveal similarly a stock set of names: Charles, Louis, Carloman, and Lothar. These were, by all accounts, the “standard” names you gave to a son who was meant to be king. Arnulf, as may be readily apparent, had a weird name compared to his relatives.

This unusual name has sometimes prompted historians to argue that this meant Arnulf was not viewed as capable of succeeding his father Carloman. It was a recognition of Arnulf’s inferior status. Yet while Arnulf did not have a standard “royal” name, Arnulf did have a very Carolingian name. By the ninth century it was known that a Saint Arnulf, the bishop of Metz, was the ancestor of the Carolingians. Saint Arnulf is perhaps better known now as Saint Arnold, the patron saint of brewers. In the ninth century, however, his role as the ancestor of the Carolingians meant that often rulers gave grants to the foundation in Metz dedicated to him. In 875 Louis the German gave a charter where the saint is described as Louis’ ancestor.1 When Charles the Bald was crowned king of Lotharingia in Metz in 869, he traced his lineage from Clovis through Saint Arnulf to himself.2

Arnulf was thus a name with important Carolingian meaning. Indeed Eric Goldberg argued that Arnulf’s father may have chosen the name precisely because it played on these Carolingian resonances: it was just Carolingian enough to be activated if he wanted Arnulf to become king, but not as full a Carolingian name as Charles or Louis.3 After Arnulf became king, writers were not shy about making the connection to the saint. Regino of Prüm, who writes a few years after Arnulf’s death, tells us that Arnulf was named after the saint not “by chance, but it was regarded as a certain presentiment and portent of the future of what he would do.”4 Naturally, Regino may be putting a nice spin on things, but the ability for Arnulf to tap into a Carolingian history like this was certainly a positive. Arnulf’s coup in 887 had set off a power scramble elsewhere in Europe, and several of these kings were emphatically not Carolingian: Odo, Rudolf, and Wido. Arnulf, despite not being a Charles or Louis, would have had a ready made method of distinction in his name.

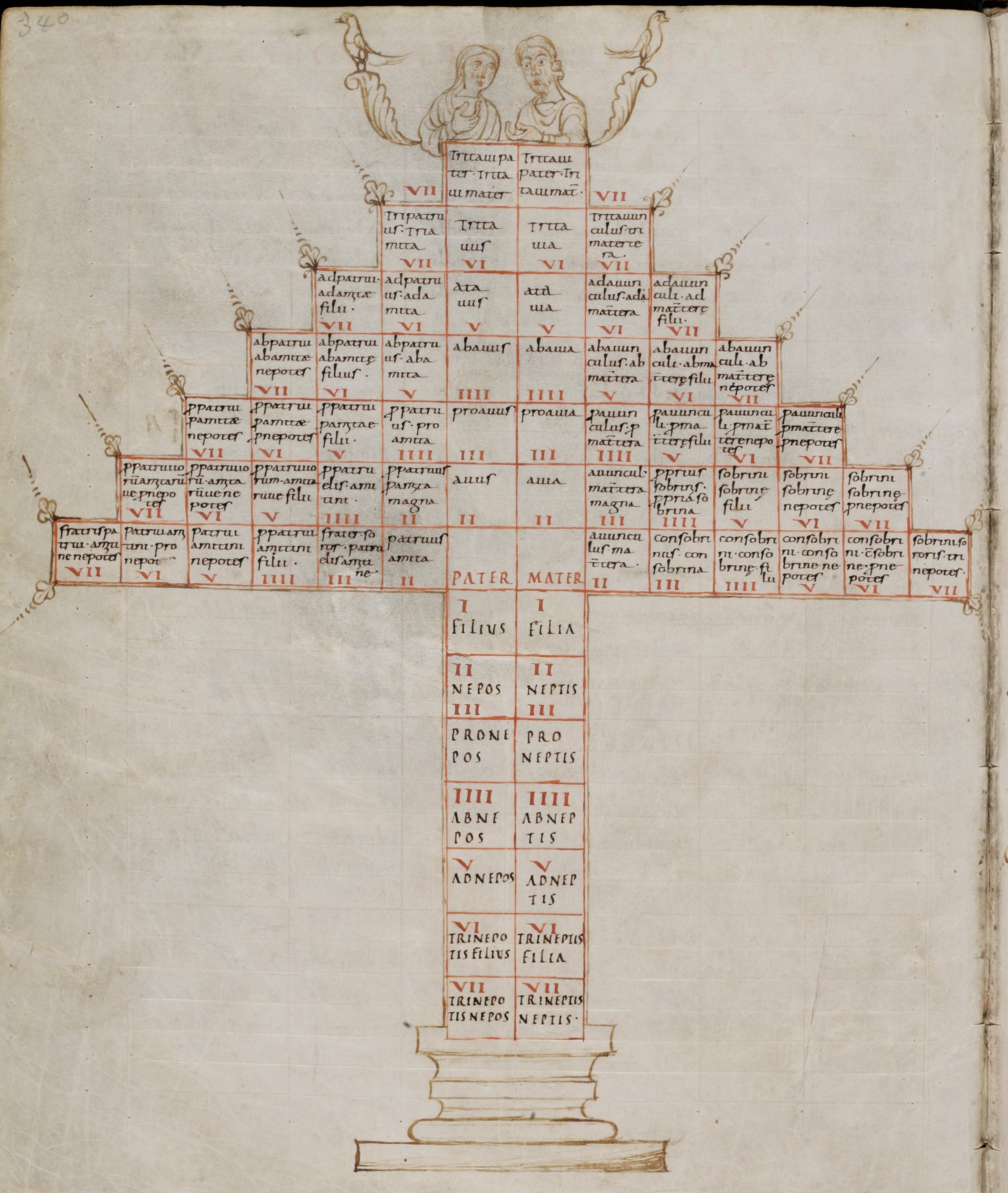

Arnulf and his court were quite keen to play up this Carolingian ancestry. A charter granted at Frankfurt in June 888 for the monastery of Prüm confirmed the charters of Pippin (noting him as Arnulf’s attavus), Charlemagne, Louis the Pious, Louis the German, Charles the Fat, Lothar I, and Lothar II (seven rulers in total). That is, almost every Carolingian king from 751 to 887 is represented here.5 The only missing ruler is Louis the Stammerer, who granted a charter in 878 which renewed the monastery’s West Frankish properties and privileges.6 This makes sense: Arnulf wasn’t king of West Francia and so he was not claiming to be an heir to this Louis. Charters often copied older charters, especially in cases of a confirmation of privileges such as this charter in 888.

What is odd is that Arnulf’s charter did not use the most recent confirmation, granted by Charles the Fat in 884.7 Instead, it ultimately went back to an older joint charter of Louis the Pious and Lothar I.8 Charles’ charter was missing a key element that Arnulf wanted to stress: the role of the Carolingians in the founding of Prüm. The charter for Louis the Pious/Lothar I stresses this element, and Arnulf’s charter copies a passage almost verbatim from it that “our ancestor king Pippin and our ancestor Bertrada” were involved in the construction of the monastery.9 That there were different potential models for Arnulf’s charter, and the one emphasizing Carolingian patronage was chosen, suggests that it was an active choice to present a specific image of Arnulf as the latest in a long line of Carolingian rulers. It also tells us something about the recipient, who must have also wanted to emphasize Carolingian patronage of the monastery. That is, it was not just an impression that Arnulf or his court advanced, but one that had buy-in from contemporaries. In placing Arnulf as a Carolingian, it also recalls the Revelatio Stephanae Papae which declared that only Pippin and Bertrada’s descendants could become kings.10 This would have contrasted Arnulf with his non-Carolingian counterparts in West Francia and Burgundy. I mean, look at their names: Odo? Rudolf? Not even illegitimate Carolingians got names like that.

Arnulf’s name, then, was certainly unusual when placed alongside a list of Lothars, Louises, and Charleses. However contemporaries likely also understood it within a longer tradition of Carolingian dynasty. Contemporaries and Arnulf’s own court were interested in drawing this connection. It would be easy to claim this was all nakedly political, that claiming Arnulf was a Carolingian would paper over his weakness. A better, I think, view is that contemporaries in the late ninth century continued to believe that the Carolingian dynasty had a special role to play, and they were not too phased by Arnulf’s peculiar name or his questionable birth status, something I discussed in an earlier post you can read here:

Indeed no one knew in 887 if the Carolingians were done for, and if you look at the map of Europe in 898 it would have appeared as if the Carolingians had regained their footing. We cannot interpret Arnulf’s reign as an intentional break from the Carolingians, because Arnulf himself believed he was the latest ruler in a line of Carolingian rulers. More than that, he saw the continuation of the dynasty as an ongoing, not failed, promise. When his son was born in 893, Arnulf had him called Louis, “the name of his grandfather.”11

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

D LG 167. ↩

AB, s.a. 869, pp. 162-163. ↩

Goldberg, Struggle for Empire, p. 265. ↩

Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 880, pp. 116-7: quod non casu accidisse, sed quodam presagio portentoque futurorum actitatum videtur. Similarly, Ermold, Carmen elegiacum in honorem Hludovici, E. Dümmler (ed.), MGH Poetae 2 (Hanover, 1884), p. 6 explains the meaning of the name Louis as a sign of the future importance of Louis the Pious. ↩

D A 29. ↩

Discussed in M. McCarthy, “Power and Kingship Under Louis II the Stammerer, 877-879,” pp. 146-148. ↩

D CF 100. ↩

D LP 251; It also bears similarities to a charter of Louis the German, D LG 134. ↩

D A 29: quod olim bonae memoriae attavus noster Pippinus quondam rex et attavia nostra Bertrada in rebus propriaetatis suae a fundamentis construxerunt. The Latin attavus can also mean “great-great-great-grandfather.” ↩

See S. MacLean’s translation of Regino, History and Politics in Late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe: The Chronicle of Regino of Prüm and Adalbert of Magdeburg (Manchester University Press, 2009), p. 127, n. 20; It is edited in G. Waitz (ed.), MGH SS 15 (Hanover, 1887), pp. 2-3. The text survives in two manuscripts, one which titles it a revelatio, and one which titles it an epistola. Regino terms it an epistola, see Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 753, p. 44. ↩

AF (B), s.a. 893, p. 122: nomine avi sui Hludawicum. ↩