Medieval Kings Were Not All Tyrants

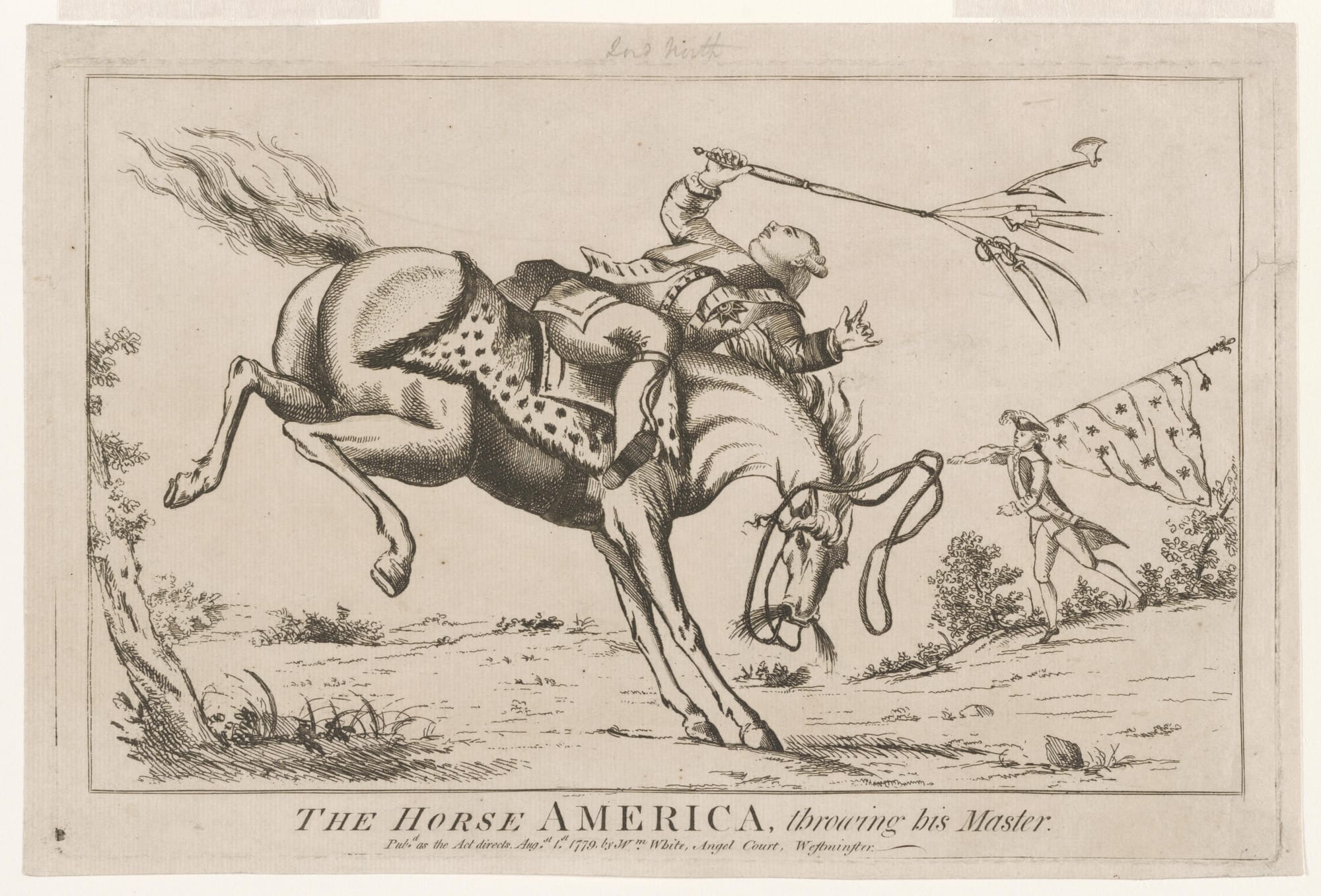

For many Americans, the meaning of a king and a tyrant are largely synonymous. It is common in American media to see kings treated as tyrannical, because they are not bound by the will of the people, are arbitrary, etc. Here is what the inhabitants of my hometown had to say, on March 29th, 1770, only a few weeks after the Boston Massacre:

The Inhabitants of the Town of Marlborough, in the County of Middlesex, being legally assembled in town meeting, and taking into consideration the deplorable and embarrassed state of America, the many distresses it lies under, the violent assaults that are made upon our invaluable rights and privileges, the unconstitutional and alarming attempts that are made by an aspiring, audacious, arbitrary power, to strip us of our liberties and all those glorious privileges, civil and sacred, which we, through the kind indulgence of Heaven, have long enjoyed, and to bring us into a state of Slavery under such Tyrants who have no bounds to their aspiring ambition, which leads them to the perpetration of the blackest crimes, even to the shedding the blood of innocents; an instance of which we have very lately had in the horrid, detestable and sinful Massacre committed in the town of Boston; and considering that our estates are not sufficient to satisfy the avarice of a growing arbitrary power, but that the lives of the harmless subjects must fall a sacrifice to the rage and fury of blood-thirsty and mercenary wretches.[1]

This excerpt is probably close to the definition of a king: an "aspiring, audacious, arbitrary power" that exists "to strip us of our liberties and all those glorious privileges, civil and sacred." Reading between the lines a bit, the Marlborough citizens were not against all kings, but specifically tyrants. Indeed, they don’t explicitly call out the king as causing the problems here. That is, they distinguished between a king and a tyrant. Medieval authors also understood kings were not all tyrants, and that there was an important distinction between the two.

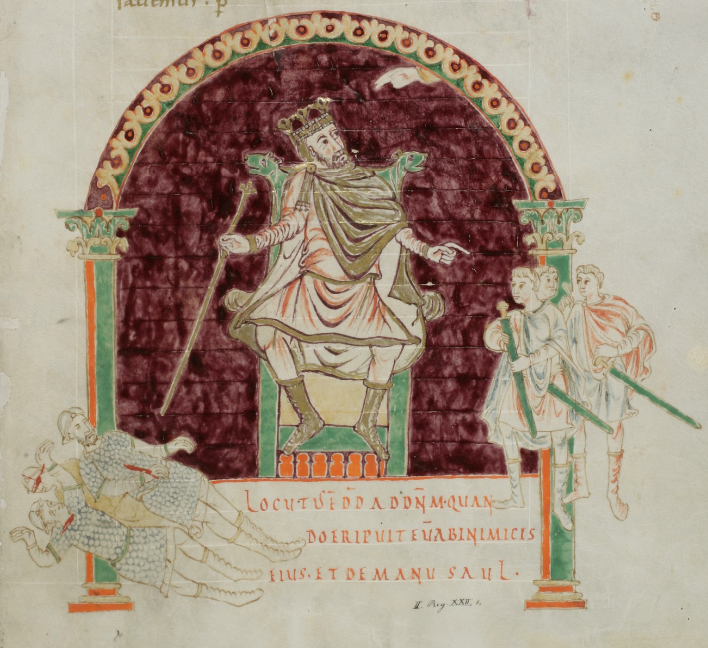

Isidore of Seville provides one definition in his 7th century Etymologies: "Kings are so called from governing...But he does not govern who does not correct; therefore the name of king is held by one behaving rightly and lost by one doing wrong."[2] Isidore relates, in a later passage, that kings were called tyrants in ancient times but "in later times the practice has arisen of using the term for thoroughly bad and wicked kings, kings who enact upon their people their lust for luxurious domination and the cruelest lordship."[3]

A few centuries later tyrannus remained a charged term, much as it would be in the American Revolution and beyond. In 879, for the first time in almost 150 years, there was a non-Carolingian king in continental Western Europe: Boso. Boso had been important at the court of Charles the Bald and under his successors.[4] Yet in 879 he proclaimed himself king, an action which met immediate hostility from the surviving Carolingians.[5] Many of the sources from the late ninth and early tenth century portray Boso as a "tyrant." Ever the polemicist, Hincmar, the archbishop of Reims who seems to have had his hand in almost everything, stresses Boso's treachery, despite being loyal to Louis III and Carloman II:

Boso, with his wife convincing [him], saying that she would refuse to live, if, [as] the daughter of the emperor of Italy and having been betrothed to the emperor of Greece, her husband was not made king, he persuaded the bishops of those parts to anoint and crown him as king, partially bound by threats, partially having been enticed by greed for monasteries and having been promised his estates and afterwards gifts.[6]

Boso is not acting on his own, but has to be goaded by his wife into action and can only accomplish his goals through threats and bribery. Hugh also draws Hincmar’s attention, but in a much shorter passage. Hincmar writes that “Hugh, the son of Lothar [II] by Waldrada, having rallied a great number of robbers, undertook to take possession of the kingdom of his father.”[7] Here too, Hincmar expresses his disapproval for Hugh by tailoring his language, describing his troops as predonum (“thieves”, “robbers”).

For all his invective Hincmar never refers to either Hugh or Boso as a tyrant. The Annales Vedastini, however, presents a similarly negative image of Boso. Boso “claimed the name of king for himself through tyranny [per tirannidem] and occupied part of Burgundy.”[8] Describing Carolingian opposition to Boso, the AV again calls Boso a tyrant in 880 and 882.[9] The Bavarian continuation of the Annales Fuldenses refers to Boso as a “tyrant” in 890 when describing his relationship to Ermengard.[10] Hugh is presented as a “tyrant”, much like Boso in the AV. Beginning in 879, Hugh “the son of Lothar by Waldrada was practicing tyranny in Gaul.”[11] This same expression gets repeated the next year.[12] In the end Hugh was blinded and then “having been thrust into the monastery of St. Boniface at Fulda, it was the end of his tyranny.”[13]

The similarity with which authors described tyrannical actions speaks to a shared set of assumptions about political authority. It was not that only Hincmar saw Boso and Hugh in a negative light, but that the annalists of the AF and AV shared a remarkably similar impression that is important. Regino, writing towards the end of the first decade of the tenth century, is very similar to the annals already described. It seems, then, that the reception of Boso (although slightly softened by Regino) and Hugh was not the product of either geography (east vs west) or time, but that it was the product of various authors’ (shared) perceptions on legitimate authority. Boso challenged the traditional claims of Carolingian kingship by claiming a kingdom of his own, and it seems clear that the various authors went to great lengths to downplay the legitimacy of this action.[14] The fact that all the sources seem to associate Hugh with followers who were either “robbers” or other unsavory characters speaks to the idea that Hugh was operating without legitimate status. In the minds of the various authors, Hugh threatened “justice and peace” in Lotharingia. Underlying this model is an idea that a rightful ruler governs with legitimate authority, but also correctly orders society in a way befitting propriety and God. Those who fail to do so, go against God and political norms, losing their claim to be called king and their exercise of political power is thus tyrannical.

Finally, under Arnulf (no post is complete without him) we have a church council held at Mainz in 888 which essentially repeats Isidore's definition and is a verbatim copy of a chapter from a synod held in Paris in 829:

So that it should be announced to our glorious lord king Arnulf, why he is king or, if you will, why he ought to be called king: He is called king by ruling rightly. For if he rules piously and justly and with mercy, he is rightly called king; if he abstains from these things, he is not a king, but a tyrant.[15]

The message is clear: only those who rule correctly are qualified to be called king. Further, good kingship is something that the ruler performs. It does not say that the king should be pious, just, and merciful, which are qualities of the person, but that he should rule that way. If the king was meant to fulfill his God given duties, he needed to act a certain way, otherwise he risked not only his soul, but those of his people.[16] As Hincmar in his On the Order of the Palace wrote, the king too would stand judgment for his actions while on Earth.[17] Steffen Patzold has argued that the Paris synod of 829 articulated a particular vision of the role of the bishops in maintaining social order within the empire. This model would then become embedded into Carolingian society.[18] In 829 Louis the Pious had been dealing with a crisis of legitimacy after a series of disasters befell the kingdom, and a series of councils were called in order to find out how to restore order to the kingdom.[19] In 888 the situation was slightly different: Arnulf needed to establish his authority after overthrowing his uncle the year before. As such it may have been an open question: would Arnulf be a king or a tyrant? Where did his authority come from? The bishops at Mainz, certainly not a neutral group, hoped to retain their influence as monitors of royal behavior, and did so by placing Arnulf in the sphere of legitimate Carolingian authority.

This is all to say, that we make an error when we simply equate a king as a tyrant. It is common in portrayals of the Middle Ages to find kings operating in just the way described by my hometown predecessors: rapacious, arbitrary, cruel, and unjust. And while I am not trying to say being a king wasn't often a brutal business, it was, our modern dislike of kings does not necessarily extend into the past. Many centuries later, John Locke would write about tyranny representing "the exercise of power beyond right."[21] As with our ninth century authors, Locke was reacting to his own political context in expounding his ideas of civil society. Our ideas of power, politics, and legitimacy are forged in the circumstances of our own times. Medieval contemporaries, and early modern ones too, did not endlessly bemoan their fate to live under a king. Indeed, for many this was a perfectly natural and just state of affairs. To medieval contemporaries "good" kings could and did rule, and our understanding of medieval political behavior shouldn't depend on a deeply cynical reading of human agency and politics. It also means acknowledging the very real limitations of medieval kings: they were not all-powerful and could be quite constrained in their actions. No ruler, at any time or in any place, is all-powerful, and that is a lesson worth remembering in our current moment. Much like today, questions of public order, political authority, and prosperity were common challenges in the Middle Ages, even if the parameters of the solutions were different. People in the past were not brainwashed or "primitive" as they are often presented, but believed in their own ideas and solutions.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can do your part in defeating the algorithm!

- Taken from C. Hudson, History of the Town of Marlborough (Boston, 1862), p. 146.

- Isidore of Seville, Etymologyies, ed. W. Lindsey, Etymologiarum sive Originum (Oxford, 1911), IX.iii.4, trans. S. Barney, W.J. Lewis, and J.A. Beach, The Etymologies of Isidore of Seville (Cambridge, 2006), p. 200: Reges a regendo vocati...Non autem regit, qui non corrigit. Recte igitur faciendo regis nomen tenetur, peccando amittitur.

- Isidore, Etymologies, IX.iii.18, trans. p. 201: Iam postea in usum accidit tyrannos vocari pessimos atque inprobos reges, luxuriosae dominationis cupidatem et crudelissimam domination in populis exercentes.

- S. Airlie, “The Nearly Men: Boso of Vienne and Arnulf of Bavaria”, in A. Duggan (ed.), Nobles and Nobility in Medieval Europe: Concepts, Origins, Transformations (London, 2000), pp. 25-42, esp. pp. 32-4; C. Bouchard, Those of My Blood: Creating Noble Families in Medieval Francia (Philadelphia, 2001), pp. 74-90. Annales Bertiniani, F. Grat, J. Villiard, S. Clémencet, L. Levillain (eds), Annales de Saint-Bertin (Paris, 1964), s.a. 878, p. 229. AB, s.a. 879, pp. 235-6.

- S. MacLean, “The Carolingian Response to the Revolt of Boso, 879-887”, Early Medieval Europe 10, no. 1 (2001): 21-48.

- AB, s.a. 879, p. 239: Interea Boso, persuadente uxore sua, quae nolle uiuere se dicebat, si, filia imperatoris Italiae et desponsata imperatori Greciae, maritum suum regem non faceret, partim comminatione constrictis, partim cupiditate illectis pro abbatiis et uillis eis promissis et postea datis, episcopis illarum partium persuasit ut eum in regem ungerent et coronarent.

- AB, s.a. 879, p. 239: Hugo etiam, filius iunioris Hlotharii ex Vualdrada, collecta predonum multitudine, regnum patris sui est molitus inuadere.

- Annales Vedastini, B. de Simson (ed.), Annales Xantenses et Annales Vedastini, MGH SRG 12 (Hannover, 1909), s.a. 879, p. 45: per tirannidem nomen regis sibi vindicat partemque Burgundiae occupat.

- AV, s.a. 880, p. 47; AV, s.a. 882, p. 52.

- AF (B), s.a. 890, p. 119.

- AF, s.a. 879, p. 93: Interea Hugo Hlotharii ex Waldrata filius tryannidem in Gallia exercebat.

- AF, s.a. 880, p. 95: contra Hugonem in Gallia tyrannidem exercentem.

- AF, s.a. 885, p. 103: in monasterium sancti Bonifatii apud Fuldam retrusus finem suae habuit tyrannidis.

- MacLean, “The Carolingian Response”, p. 24

- MGH Conc. V, no. 26, p. 255: Ut annuncietur glorioso regi nostro domino Arnulpho, quid sit rex quidve vocari debeat: Rex a recte regendo vocatur. Si enim pie et iuste et misericorditer regit, merito rex appellatur; si his caruerit, non rex, sed tyrannus est. There are manuscripts of this produced in St. Gall at the end of the 9th century.

- We see this appear as a concept during Lothar II’s attempted divorce of Theutberga in the mid-ninth century, S. Airlie, “Private Bodies and the Body Politic in the Divorce Case of Lothar II,” Past & Present 161 (1998): 3-38.

- See Hincmar, De ordine palatii, c. 3, p. 36-38.

- On the synod and this model see Patzold, Episcopus, pp. 135-68.

- On the Paris synod see De Jong, Penitential State, pp. 170-84.

- John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1689), c. XVIII. https://standardebooks.org/ebooks/john-locke/two-treatises-of-government/text/chapter-2-18