Not Quite A Review: Oathbreakers and Rebellious Sons

After a very long lapse I managed to finish reading the 2024 book by Matthew Gabriele and David M. Perry called Oathbreakers: The War of Brothers that Shattered an Empire and Made Medieval Europe. For those who are unfamiliar, it covers the years leading up to the Carolingian Civil War in the early 840s. The book ends in the late 840s, in the aftermath of the civil war but with many of the questions prompted by it still unresolved. Their core argument is that the lack of consequences for betrayals (oathbreaking) in the period before Louis the Pious' death seriously hampered the ability of the Carolingians to keep violence from spilling out. That is, because those who broke their oaths were rarely, if ever, punished for their transgressions, there was little incentive to remain loyal or to not constantly switch side. It made me wonder about the later period. Do those Carolingians have similar issues? Did they try to learn from the past?

First we need to lay out the situation before approximately 840. One common feature of Carolingian dynastic policies in the period before Louis the Pious' death in 840 was the use of what is known as a "subking," so called because they were a royal son given the title of king, but whose authority was still limited. Charlemagne had his sons confirmed as kings, but seemingly kept a tight watch on them as they learned the ropes of kingship.[1] Several advisors were sent with Louis to Aquitaine specifically to guide him.[2] Louis the Pious in turn would make his sons kings, and it is the issues with this that lay at the heart of Oathbreakers. Making a royal son a king meant setting them up with their own court, pursuing their own families, and building up elite networks centered on the son. This posed a challenge for Carolingian rulers, because if they wanted to change succession arrangements or had a new child (which both happened to Louis the Pious) then the sons, now with their own bases of support somewhat independent of the king, wouldn't be too happy.[3]

It is here that things begin to diverge: in West Francia and the middle kingdom (Middle Francia sounds decidedly wrong) there continued to be subkings, but in East Francia Louis the German never allowed his sons to use the title. One big difference is that Charles the Bald had only one main heir, Louis the Stammerer; his other son was quickly shepherded off the scene and fled to Louis the German's court. It seems that Charles tried to make his son a subking but was unsuccessful.[4] Lothar I, the eldest son of Louis the Pious and ruler of the middle kingdom, established his son Louis II as ruler of Italy and issued charters jointly with him. Lothar II would thus be heir to the Lotharingian heartlands upon Lothar I's death in 855.

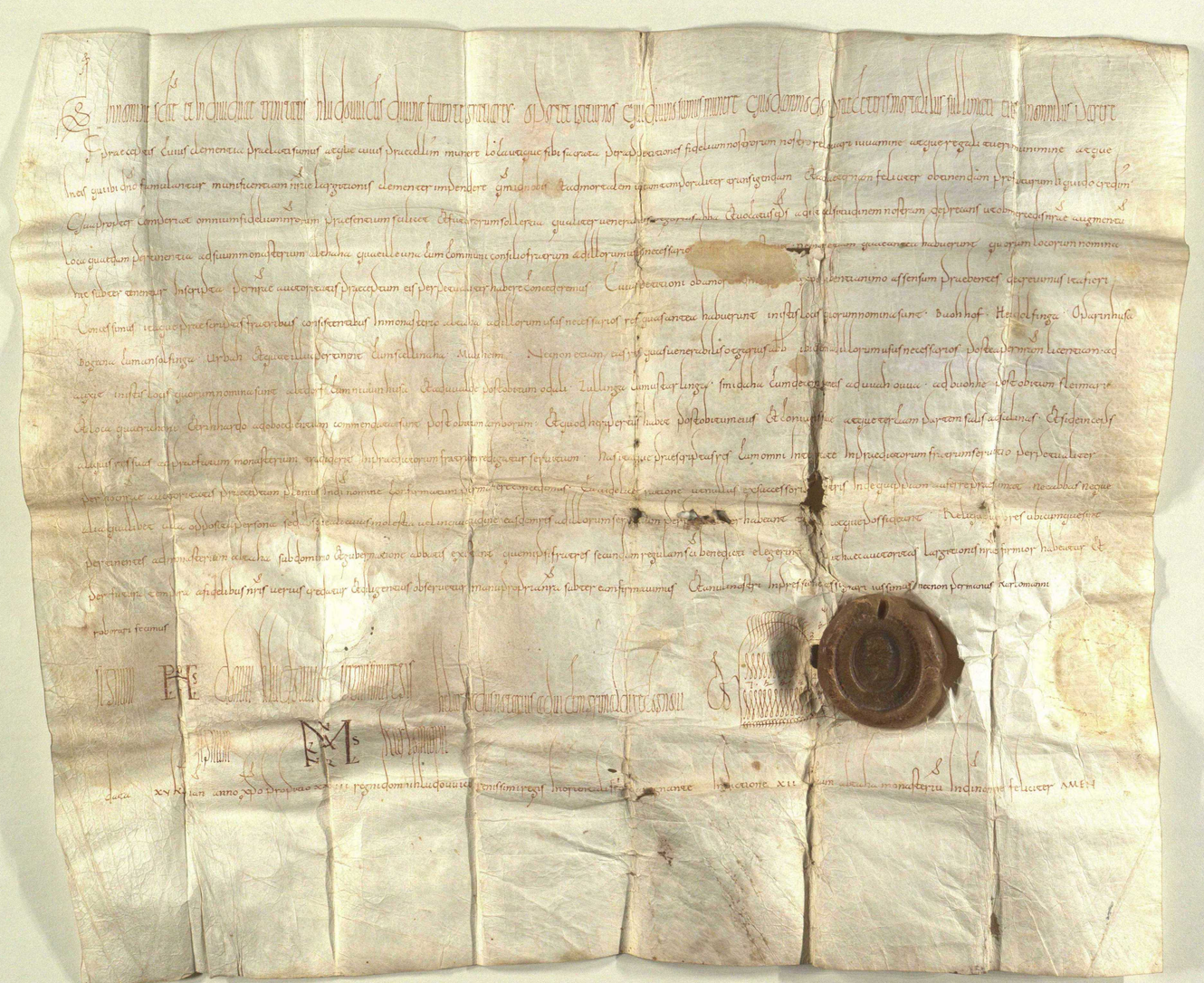

It was only in East Francia that we see something similar to the chaos of Louis the Pious' later years, but even then Louis the German was never overthrown, and seems to have tamped down most of these filial revolts. One reason, I think, that he had such success was precisely because he denied them the use of the royal title. Without letting themselves become kings before his death, it limited the options the sons had to rally supporters and create independent power bases. Yet in many ways they operated as kings, for instance their signa appear on charters relating to their future designated kingdoms. So Carloman, who would become king of Bavaria, can be found in charters for Bavarian centers during Louis' reign.[5]

Louis the German also trusted them to lead military expeditions on his behalf, especially Carloman who was "always occupied in the pursuance of wars" and "always brought back the triumph of victory."[6] Yet Louis could not count on their unquestioning loyalty. Louis ruled for ages in Carolingian terms, by 850 when Arnulf was born he had been king for a bit over 20 years already.[7] By 876 when he died, his sons were well into adulthood, presumably desirous of becoming kings in their own right. It is thus unsurprising that Louis faced a wave of discontent in the 860s and 870s.

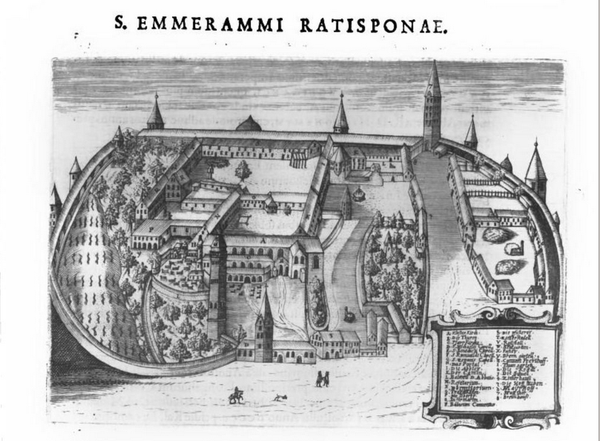

Already Carloman, Louis the German's oldest son, may have taken a mistress and had a son, the future Arnulf, as a way of rejecting Louis' tight control of the East Frankish family. It seems that Louis eventually relented to this, bringing the young Arnulf (alongside his cousin Hugh, the illegitimate son of Louis the Younger) to an assembly in 860.[8] Yet by the following year Carloman staged a major revolt. Precipitating this was likely Carloman's desire to install his own loyalists along the eastern frontier, against his father's wishes.[9] Louis had his own men along the border, meaning they were loyal to him, not Carloman. Carloman now wanted more independence and tried to outmaneuver his father. Louis responded harshly to Carloman's revolt, punishing several of Carloman's men at an assembly at Regensburg in 861. If Gabriele and Perry are right about the lack of consequences for oathbreaking causing further tensions within the empire, it wouldn't surprise me if Louis' efforts to strip honors and lands from Carloman's supporters in 861 might represent an attempt to try something different.[10] Carolingian sons were usually spared the harshest punishments, but this didn't necessarily apply to their supporters.[11] Eventually Louis quieted his eldest son's ambitions by seemingly promising him greater rewards in the form of the kingdom of Italy.[12] Carloman was also valuable to Louis as a frontier commander who allowed him to wage war elsewhere, such as in Italy or West Francia. Nevertheless, this meant Carloman had prime opportunities to strike while his father was away, as he did in 858.[13]

In the next generation the evidence is murky. Charles the Fat didn't have legitimate heirs, but there is evidence that he tried to have his son Bernard retroactively legitimized and made a subking.[14] Louis the Younger's son is hardly recorded, except to mention his death (perhaps because of Arnulf's involvement). Carloman never made Arnulf king, but placed him into a similar position as he had been: a frontier commander. I think tying this to Arnulf's illegitimacy is missing the bigger picture; East Frankish kings had already stopped having subkings anyways. Arnulf himself had his son Zwentibald made king of Lotharingia, to disastrous ends. His only legitimate son, Louis the Child, only was made king after Arnulf's death, but the elite may have sworn to make him king in 897.[15] That is, if I'm right about the policies of Louis the German and Arnulf, the impact of the choices made during the 830s and 840s continued to reverberate all the way into the 890s.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can have these posts delivered right to your inbox!

- See T. Offergeld, Reges pueri: das Königtum Minderjähriger im frühen Mittelalter (Hanover, 2001), pp. 305-315. J. Davis, Charlemagne's Practice of Empire (Cambridge, 2015), pp. 104-106. Even as adults he continued to maintain oversight, see R. McKitterick, Charlemagne: the Formation of a European Identity (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 88-102.

- Astronomer, Vita Hludowici Imperatoris, ed. E. Tremp, MGH SS rer. Germ. 64 (Hanover, 1995), cc. 3-4, pp. 288-296.

- On this see also M. de Jong, The Pentitential State: Authority and Atonement in the Age of Louis the Pious, 814-840 (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 52-58.

- Offergeld, Reges pueri, pp. 321-330.

- DD LG 110, 116, 145, 161, 163-165.

- D A 103: patre nostro Karlomanno semper in bellorum procinctu occupato; Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 880, p. 116: christianae religioni deditus...Plurima quippe bella cum patre, pluriora sine patre in regnis Sclavorum gessit semperque victoriae triumphum reportavit.

- His first charter is dated to 829, D LG 1. Generally I take issuing a charter as the beginning of a king's reign, since they had distinct forms associated with royal authority. If we discard this first charter the second is from October 830, D LG 2.

- E. Goldberg, Struggle for Empire: Kingship and Conflict under Louis the German, 817-876 (Ithaca, N.Y.; 2006), pp. 260-261.

- AF, s.a. 861, p. 55.

- AF, s.a. 861, p. 55. AB, s.a. 861, p. 85.

- B. Kasten,Königssöhne und Königsherrschaft: Untersuchungen zur Teilhabe am Reich in der Merowinger- und Karolingerzeit (Hanover, 1997), p. 511.

- This would have later consequences, in particular why Arnulf feels compelled to intervene in Italy.

- Goldberg, Struggle for Empire, pp. 264-265.

- S. MacLean, Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 129-134.

- This is a weird thing that could be its own post, but if you are dying to know you can read pp. 339-340 in my own dissertation for the evidence.