Reading Empire in the Archive

Visions of East Frankish Imperium in a Vienna Manuscript

One of the things I love to do is to question our assumptions about people’s actions and ideas. This was something that drew me to studying Arnulf in the first place: in 896, almost a hundred years after Charlemagne, Arnulf went to Rome and was crowned emperor. Why? Recently I have been working on how people in Arnulf’s day understood the imperial title. If you have heard of the Carolingians at all, you’ve probably also heard of Charlemagne’s coronation on Christmas Day 800 as “reviving the Roman empire” or some similar type of claim. There is tons of scholarship on Charlemagne’s empire, and now a decent bit on Louis the Pious too, but relatively little beyond the 840s, when the empire was divided and the imperial title began to be increasingly associated with rule over Italy specifically.

The answer to why Arnulf would want to be emperor may seem obvious: emperors are powerful, kings want to increase their power and authority, etc. To my mind, however, these are not particularly good explanations. They rely on the assumption that all rulers want the same thing, throughout time. That is, Arnulf wants to become emperor because all kings want to become emperors. Not a particularly satisfying answer. This is what I call the “Crusader Kings” approach to politics, where all rulers at all times are trying to maximize their power and expand their territory. A better answer looks at what empire actually means to late ninth century audiences, and what is to be gained by becoming emperor. Arnulf was king in East Francia, why bother with Italy at all? This question of why Arnulf cared about Italy will need to be its own post at some point, so today I want to focus instead on what I think is a specifically East Frankish view of empire that can be found in a late ninth century manuscript.

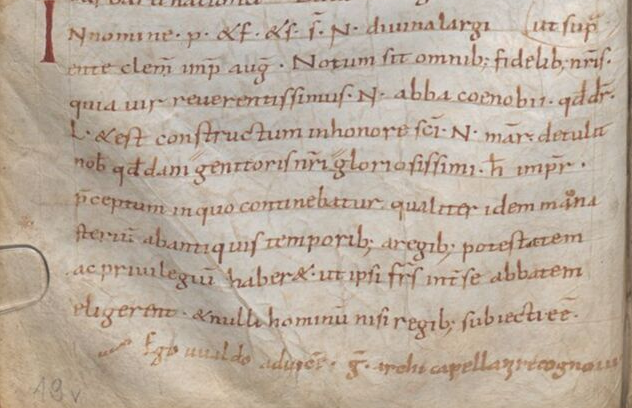

Our manuscript, now located in Vienna, is a copy of a collection of formulae, not quite medieval boilerplate form letters, but similar. Essentially they are a series of semi-anoymized guides to writing a type of charter, letter, etc. This collection in particular stems from the monastery of St. Gall, and Bernhard Zeller has argued they reveal a specific “hegemonic-imperial kingship” as a model for Arnulf.1 Zeller is interested in the different manuscripts of this collection and trying to locate a date for it. He suggests sometime after the bishop of Constance, Solomon III, became abbot of St. Gall. This places it firmly in Arnulf’s reign. The Vienna manuscript shows its connection to the monastery because a brief note, in a different hand, at the bottom of one of the pages is a recognition line for a “Waldo” and “Grimald.”

This was presumably taken from a charter of Louis the German from 861, that was granted for St. Gall. Whoever added this note must have been looking at the charters, because this is the only time Waldo and Grimald were both listed in the recognition line. This is a bit of speculation on my part, but I wonder if whoever added this note believed this Waldo was the bishop of Freising from 883 to 906, and Solomon III’s brother.2

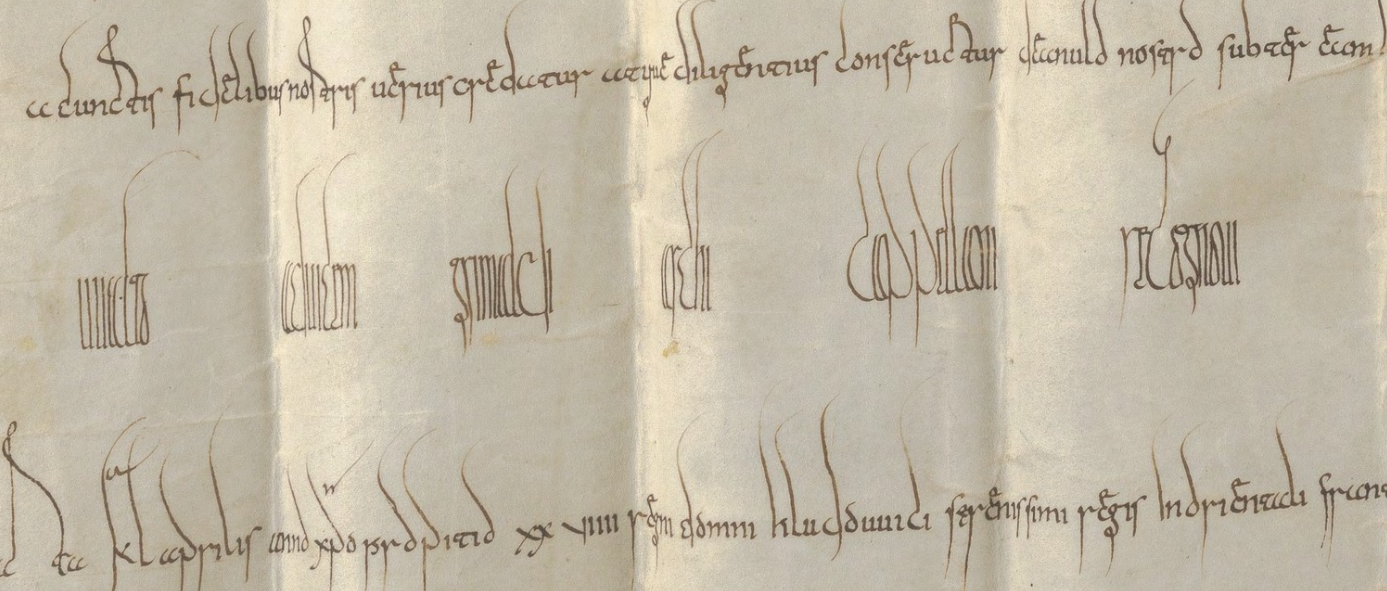

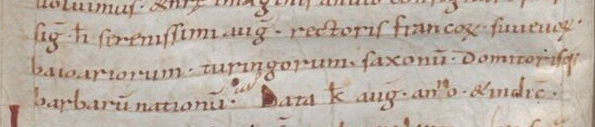

The first five formulae in the collection are for royal charters, and in our manuscript at least three of the five are ascribed to Louis the German. This isn’t true of every manuscript, in others they are ascribed to Charles the Fat. The first formula describes Louis both as “king of Germany” and as “the most serene king in East Francia” but is dated “in the fifth year of his empire.”3 The next formula has a signum line that presents a “most serene Augustus Louis leader [rector] of the Franks, Swabians, Bavarians, Thuringians, Saxons and the master of barbarian nations.”4 This is very similar to two passages of Notker’s Gesta Karoli. The first referred to Louis as “king or emperor” and then listed his rule over many peoples.5 The second described Charlemagne as the “the leader [rector] and commander of many nations.”6

This formula immediately flows without a break into another formula, this time in the name of a “clement emperor Augustus.”7 Unlike the other formulae it does not give a name for the ruler, leaving an N (for nomen) as a placeholder. It does, however, note “our father the most glorious emperor Louis.”8 Either this refers to Louis the Pious, in which case Louis the German is the emperor named in the intitulatio or this refers to Louis the German and the emperor at the beginning is Charles the Fat. Given that the preceding two formulae refer to Louis the German, it seems plausible this one does as well, but in either reading Louis the German is presented as an emperor.

These formulae as they appear in the Vienna manuscript thus present a picture of Louis the German’s rule that was firmly imperial in both terminology and ideas. By eliminating the references to Charles the Fat (except for the final formula) and casting them as charters of Louis the German, it created an impression of Louis’ rule as imperial. It is rule over multiple peoples that seems to have been a key element for later ninth century Carolingian conceptions of being qualified to be emperor. The link between multiple people and imperial rule is found in the Annales Fuldenses’ entry for Charles the Bald’s coronation in 869. According to the annalist Charles claimed the title of emperor because he possessed two kingdoms. Notker, writing for Charles the Fat in the 880s, noted that Charlemagne went to Rome “so that he who was already the ruler and commander of many nations might obtain more gloriously by apostolic authority the name of emperor.” This is the same line that is echoed in the formulary collection.

Louis the German never actually used the imperial title, and was never crowned emperor, but did have imperial aspirations especially for his son Carloman. Louis the German held negotiations with the actual emperor of Italy, confusingly also named Louis (II of Italy), to name Carloman as the emperor’s successor.9 If you are an eagle-eyed reader, you will remember that this Carloman is none other than Arnulf’s father. The elision of Charles the Fat in the Vienna manuscript makes sense if the goal was to present Arnulf as the successor to Louis the German. Charles the Fat was emperor, but his empire also included West Francia. The Vienna manuscript created a specific image of East Frankish empire that could be applied to Arnulf. By retroactively presenting Louis’ kingdom as an empire composed of multiple peoples, it created an imperial model for Arnulf’s own kingdom in the 890s.

I hope you liked this post! Please consider subscribing and/or sharing it widely! Have a burning Arnulf or early medieval politcs question? Leave a comment and I may turn it into a post!

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! Subscribe to receive new posts and support my work!

B. Zeller, “Nach 887/888: Herrscherbilder und Herrschaftskonzeptionen in der sogenannten Collectio Sangallensis,” in W. Pohl, M. Diesenberger, and B. Zeller (eds), Neue Wege der Frühmittelalterforschung: Bilanz und Perspektiven (Vienna, 2018), pp. 373-382 at p. 378. Zeller is building on the suggestion by A. Rio, Legal Practice and the Written Word in the Early Middle Ages: Frankish Formulae, c. 500-1000 (Cambridge, 2009), pp. 152-160. ↩

The charter is D LG 103. Waldo was a subdeacon who wrote three of Louis’ charters, but the other two are alongside Witgar, not Grimald. DD LG 94 and 97. ↩

Vienna Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 1609, fol. 18v: signum hl serenissimi regis in orientali francia. Dato kl maii anno imperii eius V ↩

Vienna Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 1609, fol. 19v: signum hl serenissimi augusti rectoris francorum suuevorum baioariorum turingorum saxonum domitorisque barbarum nationum. ↩

Notker, GK, II.11, p. 67: rex vel imperator. ↩

Notker, GK, I.26, p. 35: rector et imperator plurimarum erat nationum. ↩

Vienna Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 1609, fol. 19v: clementia imperator augustus. ↩

Vienna Österreichische Nationalbibliothek 1609, fol. 19v: genitoris nostri gloriosissimi hl imperatoris. ↩

Convincingly laid out in Eric Goldberg’s Struggle For Empire, pp. 304-334. ↩