Schrödinger's Royal Heir: Succession and Medieval Political Crisis

It was a November day when the unified Carolingian empire came to a final end. The last emperor to rule the entire realm, Charles the Fat, found himself on the wrong side of a political coup led by his own nephew Arnulf of Carinthia. On November 27th, 887 Arnulf granted his first charter where he used the title of king. The opening of the charter, called the arenga, lets the reader know that Arnulf "by a certain divine grace [was] placed in front of other people."[1] It was not just the elites who marched with him to Frankfurt that made him king, but God too.

Let's back up a bit, however. How do you become a king in the middle ages?[2] Succession in the medieval world was not always an easy or smooth process. Medieval politics revolved around the court and the political networks that extended through the king. The king was a prime source of patronage, meaning access and proximity to the king could bring great benefits.[3] If you weren't close to the king himself, you could always try to become close to his heir. This is all well and good until the king does something unfortunate like having two sons. Now, people have to decide. Do you follow prince A or prince B? In some cases both will inherit, in others only one. The situation gets even more complicated if powerful, and ambitious, relatives remain alive with their own claims to the throne.

As the king grows old, or gets ill, this creates a political crisis in waiting. For the East Frankish Carolingians this posed a recurring issue in the late 870s and 880s as Carloman and Charles the Fat were both ill, leaving the succession an open question. In Charles' case we know that he tried to make his son Bernard his legitimate heir, but was thwarted by some unnamed bishops and the untimely death of a pope.[4] This provided an opening for Arnulf, who had been denied the throne by his uncles since Carloman's illness in 879. Arnulf's own illness from 896 to 899 prompted him to secure elite approval for his young son Louis.

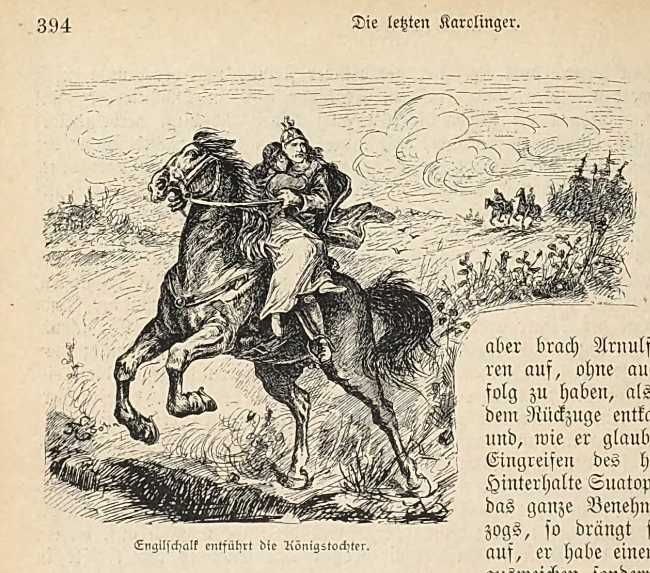

This meant that succession provided an opportunity for has-beens and would-bes to change their fortunes. A courtier who had lost favor could place their hopes in the king's son, hoping for a restoration to power and office. Rival factions of elites formed around differing throne-worthy candidates in a whole bunch of places such as Italy in the mid-870s and West Francia in both the late 870s and the 890s, to give just a few examples.[5] Indeed the Wilhelminer seem a prime example. This family had been shut out of power in the 870s, but reappear as allies of Arnulf in the 880s and beyond.[6] It seems likely that they were hoping Arnulf's rise would restore them to power. This did work, temporarily, but one member of the family, Engelschalk II, got into hot water first by kidnapping Arnulf's daughter and then angering the leading men of Bavaria, who seized and blinded him.[7] Soon after other members of the family were killed, leading to the seemingly end of the family's fortunes. The heirs themselves could be more or less established, creating a situation where they were both powerful but not guaranteed a royal throne.

As might be guessed from the case of the Wilhelminer, being crowned was not the end of the road for the new king. Instead, the act of becoming a king could be long and drawn out depending on the circumstances. One of the first things a new king does is rearrange the court, keeping some old partisans and installing new ones. Louis the Pious famously purged the court of his sisters, perhaps because of their influence during the last years of Charlemagne's reign.[8] Hincmar, one of the most important counselors for Charles the Bald before relations cooled in the 870s, attempted to stay relevant with the young king Carloman II by writing the De ordine palatii.[9]

The tumultuous period after Charlemagne's death, when it seems conditions on the ground were less receptive to Louis than might be assumed, and in the 870s, highlights how even when things go "right" succession was a moment of extreme danger. Succeeding in succession was largely about a few things: first, managing elites. An heir who quickly alienates the magnates will have a bad go of things. Smart management is in order. Charles the Fat had to deal with this several times, taking over the kingdoms of Italy and West Francia. Both regions posed a challenge because the elites were accustomed to having a much closer ruler. Some elites, however, preferred to keep the king at arms length: Arnulf's son Zwentibald learned this the hard way in the latter half of the 890s.[10] It was common for kings to use charters to create relationships between key institutions/magnates and the court.[11] We see Charles the Bald and Louis the German do this in their own respective kingdoms, and naturally Arnulf too.

All this to say, becoming king was no small task, but required a lot of things to go right, even for those who were meant to become king. Those who were actively denied succession needed to overcome additional challenges. The reason for coronations, assemblies, etc. was that they operated as what I'll call a "stabilizing ritual."[12] These served to reaffirm the proper order of society, with the king at the center/top. It was important that they designated the acceptance of the ruler by the elite. The more that agreed, the more "inevitable" their claim to power may have looked. Protracted conflicts and rapid switching between candidates, such as the Anarchy in England or the Carolingian Civil Wars, solidified the impression of a fractured political and social order. Often threatening and destabilizing because of their power and potential, but never guaranteed to become a ruler either, royal sons functioned as something of a Schrodinger's heir.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can have these posts delivered right to your inbox!

- D A 1: Oportet igitur, ut, quia quodammodo divina sumus gratia caeteris mortalibus praelati, hi qui fideliter nostro parent imperio, nostram sibi sentiant usquaque suffragari clementiam.

- A good recent book on the later period is B. Weiler, Paths to Kingship in Medieval Latin Europe, c. 950-1200 (Cambridge, 2021).

- At least under more powerful and established rulers, in some places the lack of patronage is taken as evidence for weak kingship. But that is another post.

- S. MacLean, Kingship and Polities in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire (Cambridge, 2003), pp. 129-134.

- In Italy see S. MacLean, "'After his death a great tribulation came to Italy...': dynastic politics and aristocratic factions after the death of Louis II, c 870-c 890," Milennium 4 (2007): 239-260; For West Francia in the 870s see M. McCarthy, “Hincmar’s Influence during Louis the Stammerer’s Reign,” In Hincmar of Rheims, edited by R. Stone and C.West (Manchester University Press, 2015), pp. 110-128 and in the 890s see H. Lößlein, Royal Power in the Late Carolingian Age: Charles III the Simple and his Predecessors (Cologne, 2019), pp. 32-76.

- Goldberg, Struggle for Empire, pp. 278-288 and H. Wolfram, Arnulf von Kärnten: eine biographische Skizze (Ostfildern, 2024), pp. 116-120. ↩︎

- AF (B), s.a. 893, p. 122.

- See J. Nelson, "Women at the Court of Charlemagne: a Case of Monstrous Regiment?" in J. Nelson (ed.), The Frankish World, 750-900 (London, 1996), pp. 223-242.

- See J. Nelson (trans.), The Annals of St-Bertin (Manchester University Press, 1991), 12.

- M. Innes, "People, Places, and Power in Carolingian Society," in M. de Jong et al., Topographies of Power in the Early Middle Ages (Leiden, 2001), pp. 397-438.

- Geoffrey Koziol calls these types of charters "accession" and "succession" acts, The Politics of Memory and Identity in Carolingian Royal Diplomas (Brepols, 2012), pp. 63-118.

- On rituals as political communication see G. Althoff, Die Macht der Rituale: Symbolik und Herrschaft im Mittelalter (Primus, 2013), pp. 32-67.