"The Chief Seat of the Eastern Kingdom": Place and Political Networks

In a modern world of instant communication technologies, aircraft, and cars, it is easy to take for granted the speed at which the modern world works. A journey that takes hours today may have taken days, or even weeks or months in the past. This can cause us to downplay the role of individual centers and places as important for politics. Even today specific places can conjure up political meaning. In an era before mass media, the physical setting was perhaps even more important as it communicated messages to attendees from far off who came to meet the king. Carolingian palaces such as Aachen could serve as venues to awe foreign envoys by demonstrating the magnificence of the ruler.[1]

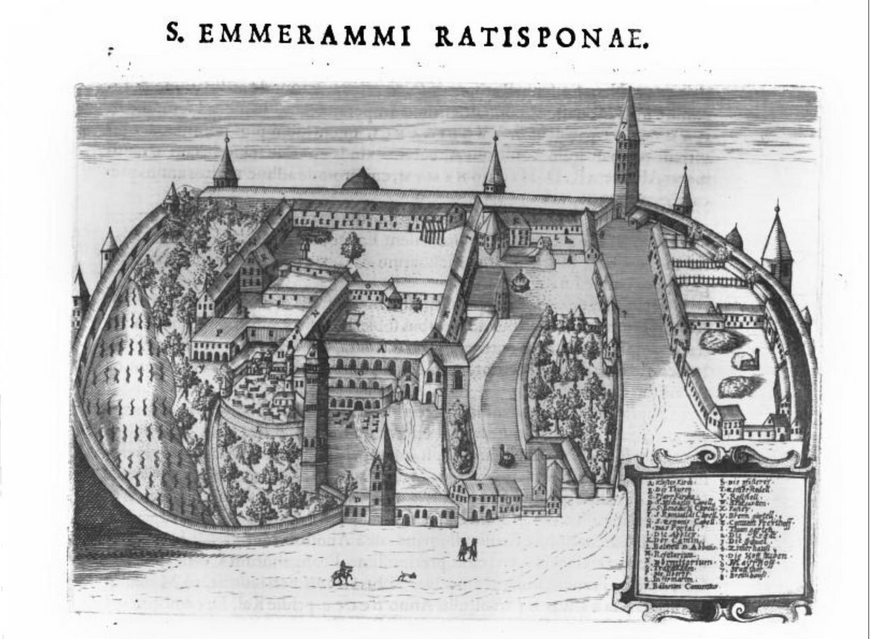

In East Francia the central place, as Regino tells us, was Frankfurt: "chief seat of the eastern kingdom."[2] Looking at Arnulf's reign, however, the chief place looks much more like Regensburg, not Frankfurt. Is Regino wrong? Why would Arnulf prefer one over the other? A few weeks ago I wrote about some charters relating to St. Emmeram's monastery in Regensburg (check it out below if you haven't read it!), and a while back I wrote about Arnulf's burial at the same monastery. What I haven't done, however, is explain the role of Regensburg in Arnulf's reign.

Under Louis the German Frankfurt had an important role in politics, but Regensburg too was influential.[3] In terms of charters granted, Frankfurt surpassed Regensburg as a center of issuance: 44 to 39.[4] Between the two places this amounts to 83 of Louis' 168 charters, or a bit under half of this charters were granted at one of those places. Under Arnulf the pattern is reversed with more charters granted at Regensburg (55) than Frankfurt (28).[5] By coincidence, this is the same overall number of charters (83) and similar percentage (out of 166 total) but Regensburg has taken on an increased role for granting charters.

Yet these numbers conceal something about when Arnulf used Frankfurt and Regensburg. 22 of the 28 charters granted at Frankfurt came in the years 887 to 889. This was the critical first few years of his reign when Arnulf issued a massive number of charters. Regensburg, on the other hand, was still used in this early period, but became more influential as time went on, and during Arnulf's final years almost all charters were granted there.

So why would Frankfurt be so commonly used at the beginning of Arnulf's reign and not the end? It is peculiar that after 889 there are barely any granted there: one in 891 and 893; two in 892 and 897. Most likely, the reputation of Frankfurt as expressed by Regino was real. Holding assemblies and granting charters there was a way of demonstrating Arnulf's newfound authority over East Francia. The charters granted there attest to a variety of magnates from different parts of the kingdom. As such Arnulf was performing his royal duties not only at the assembly, conferring with his elites, but by displaying his generosity. Or, he was trying to convince any would-be fence dwellers that his side was better: one source reports that Arnulf began to confiscate land from those who didn't support him.[6] Frankfurt's reputation as a center of East Frankish royal power would have solidified Arnulf's claim to authority.

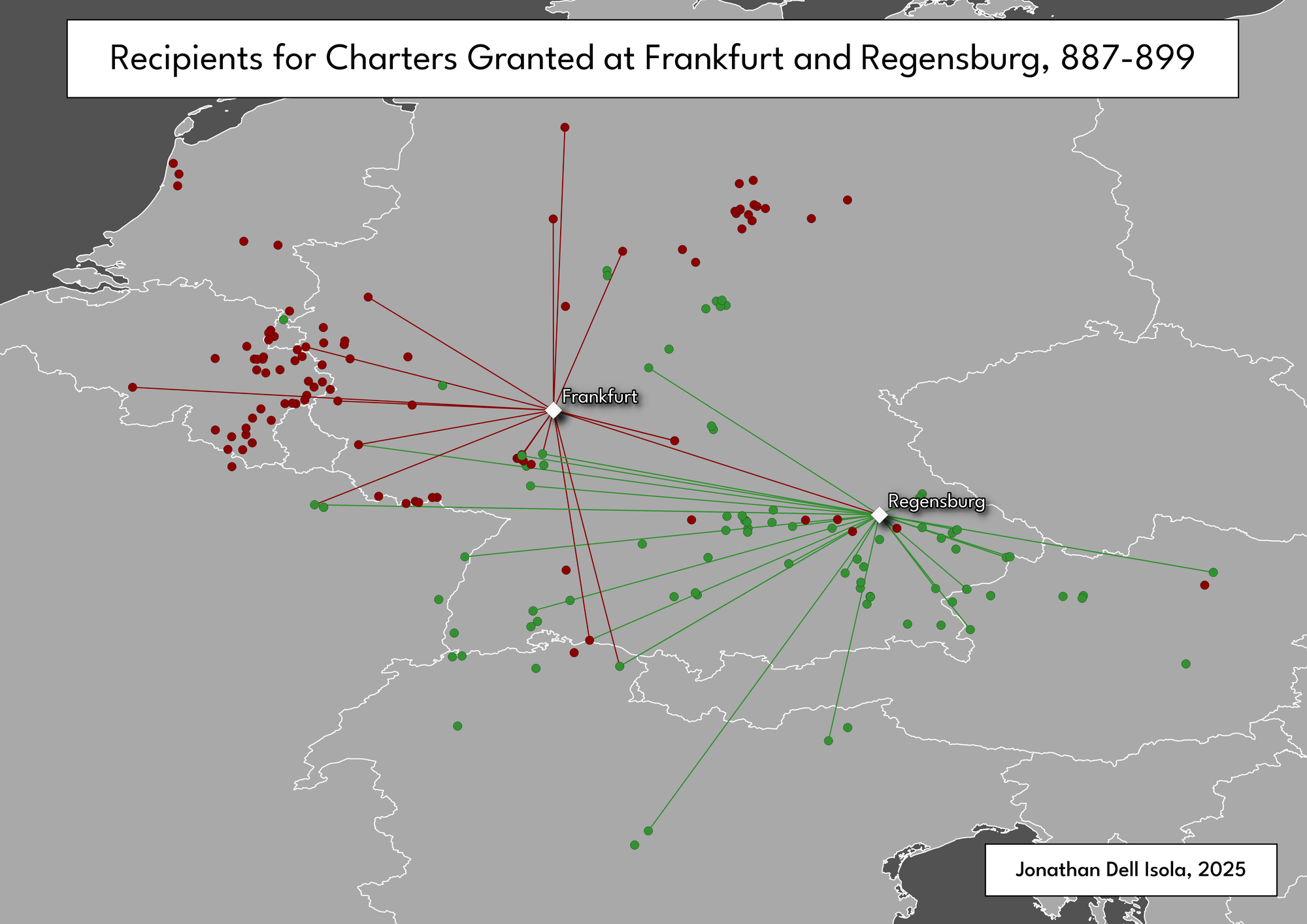

It is likely also that that the usage of Frankfurt was tied to the nature of Arnulf's early years, when a non-Carolingian king in Burgundy seemingly claimed Lotharingia as well. Frankfurt was closer to Lotharingia than Regensburg, making it easier for magnates to travel there for assemblies.[7] When Lothar II came to Louis the German in 855, along with some Lotharingian magnates, in order to secure Louis' sanctioning of his kingship, he went to Frankfurt.[8] Possibly, Frankfurt was a convenient location for these types of assemblies, and we can see this potentially reflected if we look at a map which shows the recipients of charters and the lands granted in those charters:

The map reveals some of the spatial dimensions at play. Recipients and lands for Frankfurt tend to be more to the north and west, while those for Regensburg tend more to the south and east. That is, the map is revealing something about how these centers fit into political networks. Several of these charters from Frankfurt came in the context of assemblies Arnulf held there in 888 and 889, both opportunities for him to demonstrate his mastery over the newly acquired kingdom. Rudolf's coronation in 888 even prompted Arnulf to send troops to the region. Before full warfare broke out Rudolf managed to secure a negotiation with Arnulf through the help of some Alemannians and avoid conflict (for the time being).[9]

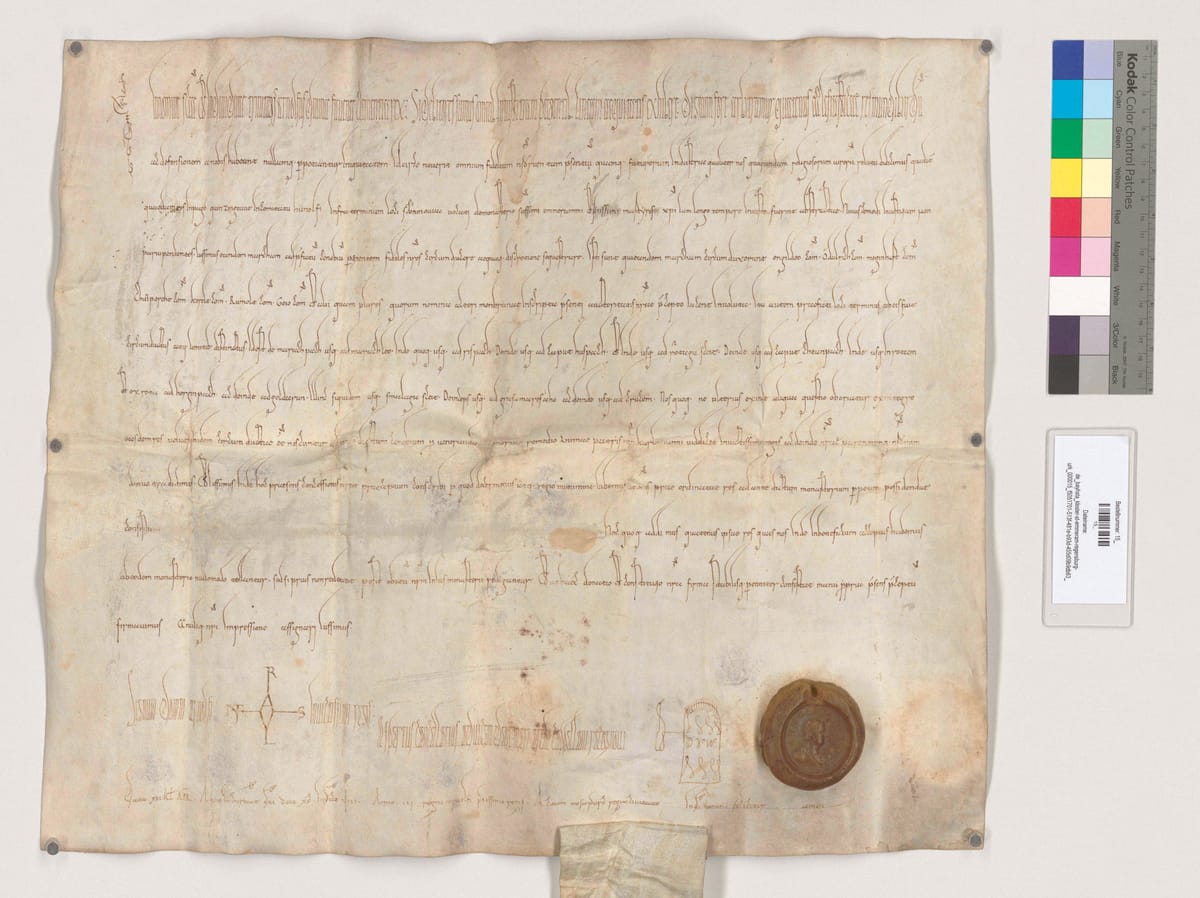

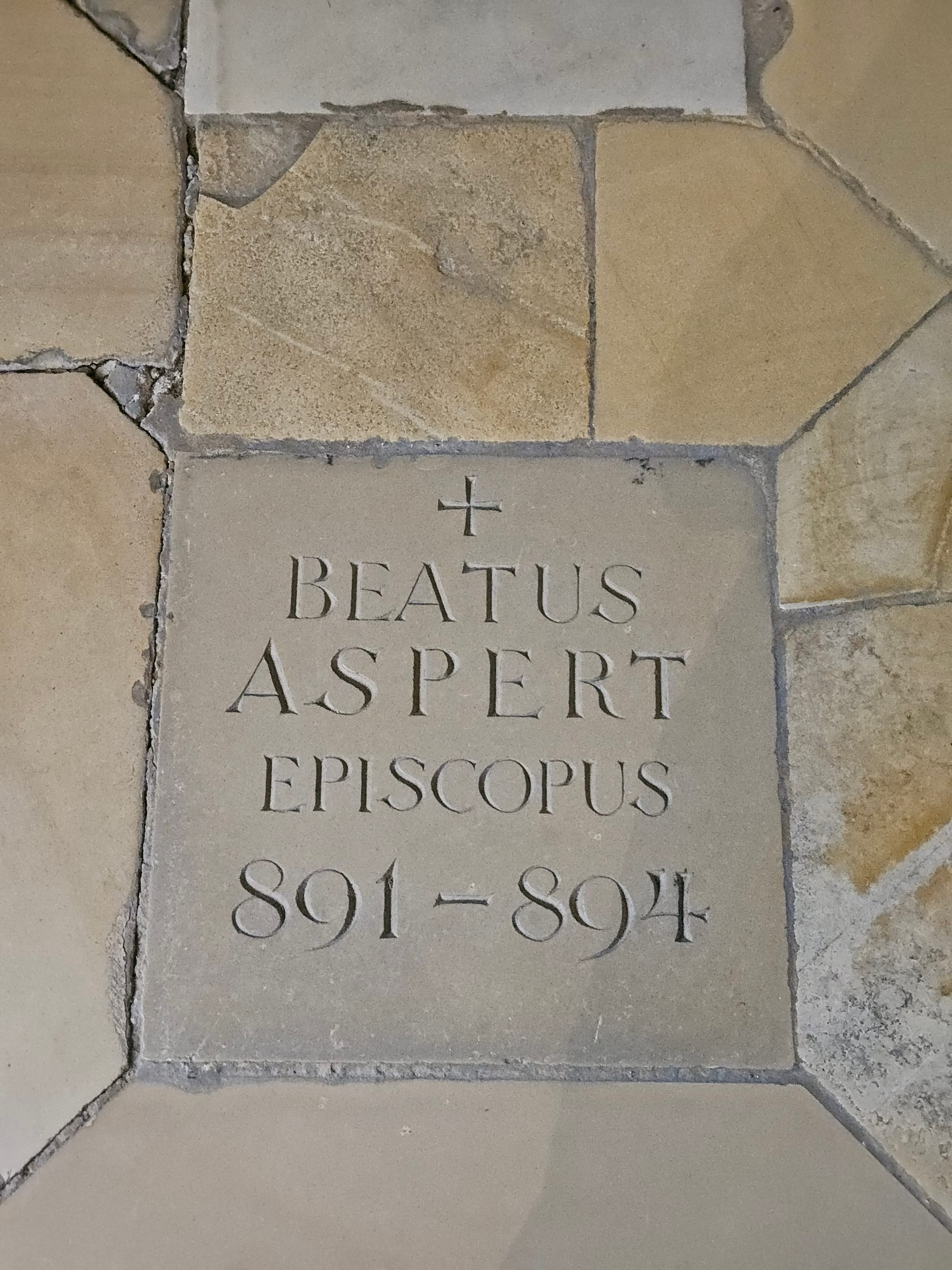

The points of overlap are also of interest: they are generally important centers in their own right (St. Gall, Reichenau, Worms, Lorsch). From this map we can catch a glimpse, perhaps, of the different elite networks that were woven together by Arnulf during his reign. The first was largely to the west and north of the kingdom, covering places such as Saxony and Lotharingia which centered on Frankfurt. The second was the area around Regensburg, which extended somewhat into Alemannia and to the eastern frontier. As I mentioned above, Arnulf issued more charters at Regensburg than his grandfather, probably because Arnulf had more local political connections in the region. Before he became king we can find Arnulf in Regensburg private charters, and after becoming king he had dealings with the bishop there.[10] After 891 it seems that Arnulf expanded the royal palace there, and his archchancellor Aspertus became bishop around the same time.[11]

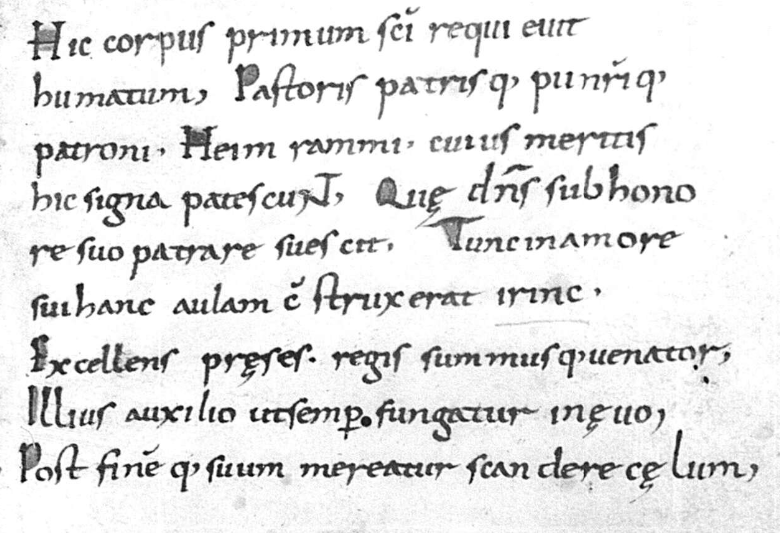

It is probably not an accident, then, that Arnulf chose Regensburg. Not only did he have longstanding connections to the city, it was already a center of power within Bavaria dating back to before it was part of the Carolingian empire.[12] Saint Emmeram in particular was also perhaps associated with East Francia: in 869 Gundachar, a rebellious nobleman who betrayed Louis the German, fell in battle because the saint held him down to be killed by Louis' advancing armies. In thanks to the saint Louis had the bells in Regensburg rung.[13] Arnulf was likely part of his father's court in 869 (in Bavaria), perhaps around the age of 19, and it seems that he carried a connection with the saint throughout his life. An eleventh century source written by a monk at St. Emmeram tells us that Arnulf thought the saint was not only his personal protector, but the protector of the entire kingdom.[14] It was also during Arnulf's reign that a new sarcophagus was commissioned for the saint by his venator and count Iring.[15]

This is all to suggest that the amount of charters at Regensburg can reflect two things: first, that it was part of the localized Bavarian political network. Regensburg's location served as a useful anchoring point in the landscape but its increased importance from the reign of Louis the German suggests that Arnulf's network of support was likely different from that of Louis', skewing more to the southeast. Second, that the choice of Regensburg was not accidental but intentional. That Arnulf built a palace there reflects this intention. Further, Arnulf had overthrown his uncle Charles the Fat at Frankfurt in November 887, yet he held his first assembly at Regensburg.[16] It took about two months to plan this assembly, meaning it was likely choreographed more maximum impact. To choose Regensburg reflects Arnulf's political priorities but also the value he placed on holding it at that specific center.

Political power is modified and channeled by space. The topography of a region, such as Italy, created different challenges for maintaining authority. Yet places had their own symbolic and political functions. Charles the Fat symbolically progressed through Carinthia to emphasize his dominance over Arnulf in the wake of the Wilhelminer War, and Arnulf would conduct a similar exercise in his own reign.[17] The contest over Aachen between Charles the Bald and Louis the German was about resources but also symbolism.[18] Space was imbued with meaning, even if sometimes we can't recover their significance as easily. It is on that point I'd like to end: to contemporaries these places were meaningful. Did Arnulf have fond memories of Regensburg from his childhood? Did he share moments of bonding with other Bavarian elites there? Those avenues of investigation are largely closed off to us by our sources, but I would be willing to bet that some of the important magnates in Arnulf's reign had longer histories with him that weaved through Regensburg. To us in the present these choices are abstracted, often understood through cultural or political lenses, but to the people in the past they could also be deeply personal choices too.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can do your part in defeating the algorithm!

- Janet Nelson, "Aachen as a Place of Power," in Mayke de Jong, Frans Theuws, and Carine van Rhijn (eds), Topgraphies of Power in the Early Middle Ages (Brill, 2001), pp. 219-222. ↩︎

- Regino, Chronicon, s.a. 876, p. 111: principalem sedem orientalis regni. ↩︎

- See Thomas Zotz, "Ludwig der Deutsche und seine Pfalzen: Königliche Herrschaftspraxis in der Formierungsphase des Ostfränkischen Reiches," in W. Hartmann (ed.), Ludwig der Deutsche und seine Zeit (Darmstadt, 2004), pp. 27-46. ↩︎

- Frankfurt: DD LG 13-15, 34, 41-43, 47, 50, 68, 74-76, 89-93, 95-97, 103, 105, 106, 108, 117, 118, 122, 123, 130, 134, 140-142, 144-146, 153, 157-160, and 162. Regensburg: DD LG 2, 6, 8, 10-12, 20, 35, 37, 39, 40, 44-46, 48, 58-60, 62, 64-67, 86-88, 100, 101, 110-113, 119, 121, 124, 125, 129, 161, and 165. ↩︎

- Frankfurt: DD A 1, 26-34, 53-57, 63-69, 86, 105, 106, 110, 157, and 158. Regensburg: DD A 5, 7, 8, 10-15, 22, 23, 38, 40, 45, 73, 74, 76, 77, 81-85, 87, 88, 90, 99, 100, 115-117, 119, 129-131, 136, 144, 145, 148-151, 159, 160, 165-175. ↩︎

- AF (M), s.a. 887, p. 106. ↩︎

- I don't have time to go into it here, but it is curious Arnulf did not choose a more centrally located palace such a Worms, even if he traveled there later in 888. ↩︎

- AF, s.a. 855, p. 46. ↩︎

- AF (B), s.a. 888, p. 116. ↩︎

- Widemann, Die Traditionen, nos. 86, 102, 132. and 163. ↩︎

- Max Piendl, “Die Pfalz Kaiser Arnulfs bei St.Emmeram in Regensburg” (1962) and Peter Schmid, Regensburg: Stadt der Könige und Herzöge im Mittelalter (Verlag Michael Lassleben Kallmünz Opf, 1977), pp. 53-58. ↩︎

- Peter Schmid, “König-Herzog-Bischof Regensburg und seine Pfalzen,” in Lutz Fenske (ed.), Deutsche Königspfalzen: Beiträgre zu ihrer historischen und archäologischen Erforschung. Vol. 4 (Göttingen, 1963), pp. 53-80. ↩︎

- AF, s.a. 869, pp. 67-68. See also Peter Schmid, Regensburg: Stadt der Könige und Herzöge im Mittelalter (Verlag Michael Lassleben Kallmünz Opf, 1977), pp. 435-440. ↩︎

- Arnold of St. Emmeram, De miraculis beati Emmerami, MGH SS 5, p. 551. ↩︎

- Munich, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 14747: https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/view/bsb00096536?page=330,331. See E. Goldberg, In the Manner of the Franks: Hunting, Kingship, and Masculinity in Early Medieval Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020), p. 186. ↩︎

- The evidence for the coup happening at Frankfurt is somewhat disputed, but I think credible. See Simon MacLean, Kingship and Politics in the Late Ninth Century: Charles the Fat and the End of the Carolingian Empire (Cambridge, 2003), p. 194. ↩︎

- For Charles the Fat see MacLean, Kingship, pp. 139-140. For Arnulf see DD A 117-120 and for context see my dissertation, "From Usurper to Emperor," p. 175. ↩︎

- Matthew Innes, “People, Places and Power in Carolingian Society,” in de Jong, Theuws, and van Rhijn (eds), Topographies of Power, pp. 397-438 and Simon MacLean, “Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, c. 850-c. 1050,” History Compass 11, no. 6 (2013): 443-457. ↩︎