What if History Turned Out Different? The (In)validity of the Counterfactual

I leave to several futures (not to all) my garden of forking paths - Jorge Luis Borges, "The Garden of Forking Paths."[1]

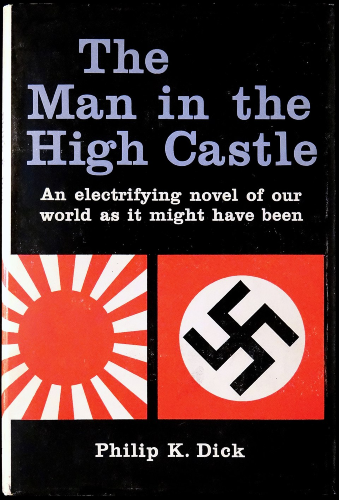

It is a staple of popular internet videos and posts: what if history happened differently? What if the Germans had won WWII? What if the French Revolution never happened? Sometimes this is the fodder for works of fiction, such as The Man in the High Castle or the even more fantastical setting of the miniature game Trench Crusade. Yet the study of a "what if" is also a controversial historical method, known as counterfactual history.[2] Put another way, counterfactual history is "a historical narrative of events that never occurred."[3] I won't go into the formal philosophical explanations of this (it doesn't make for great reading)[4] but I do want to explain what counterfactual history is, some of its criticisms, and how I think it can be useful within certain limitations.

Part I: What is Counterfactual History?

Cass Sunstein argues that even normal historical explanations involve a sort of counterfactual reasoning: shifting through potential causes and effects and creating a narrative from them.[9] In fancy-sounding academic language it is what I call "an epistemology of the possible." An epistemology of the possible is a useful tool in the historians' utility belt. Instead of seeing history as deterministic, one event inevitably leading to the next, keeping in mind the idea of the possible helps prevent such a view. Simon Kaye sees counterfactual history offering three benefits for testing ideas about historical change:[10]

- The assumption that a historical process or event is indispensable to historical outcomes

- The assumption that two events are causally related

- The assumption that events were inevitable

Daniel Nolan even suggests reasons counterfactuals are helpful when we can't determine if they are true or false because they help question assumptions and increase our awareness of contingency.[11] Contingency is one of the core challenges every historian has to grapple with. In other words, is the future determined or malleable? Reading history may make it appear like a grand narrative, but historians are often mired in the evidence trying to sort out the chain of events and to give them reasoning. Or, as Nolan puts it: "History, as it is practiced, cannot do without causal judgments."[12] This is also what distinguishes counterfactual history from alternate history: the former is concerned with a "change in an existing causal change, leading to a whole series of consequent changes" while the latter is about suggesting "a world parallel to our own without enquiring too closely how it came into being."[13]

To return to Sunstein's point that essentially all history engages in counterfactuals, we get somewhat towards the core of what history actually is. Evaluating the connections between events, processes, individuals, texts, and artifacts is critical to historical inquiry. In both cases, this work of analysis depends on understanding (or believing to) human behavior, comparisons between times and places, and a bit of the historian themselves.[14] Further, almost by necessity this work of analysis cannot be done without attributing causes to events and actions. How does one know what a text means without attributing some type of motivation to the language used, the medium, or the transmittance of it to the present? At some point, the historian needs to declare a causal relationship, whether implicitly or not. There can be no "statement of facts" independent of those types of judgments.

Part II: Critiques of Counterfactual History

The critiques of this method are somewhat straightforward: that it ignores historical context at best, and is little more than imagination at worst. This is because counterfactuals depend on analyzing the causes of historical change. To ask "would the US be different if Al Gore had won the 2000 presidential election?" is to engage in an analysis of cause and effect. What would be different? What would be the same? Obviously, how can we know what would happen? In short, we can't. To make an argument about what might have happened is to make assumptions about historical actors' choices. Done badly, this can mean flattening context or denying agency to other actors to create an imagined narrative. As Matti Bunzl writes, "a counterfactual inference is only as good as the assumptions that one makes about background conditions."[5] Bunzl's point is that if we are to suppose an alternate past, say "what if the British developed nuclear weapons in 1939?" then we also need to create a plausible set of circumstances that led to that alternate past. In the process of reasoning (or imagining) those circumstances, we have strayed far from reality. Bad counterfactual takes on the form of a capriccio, a painting where buildings, ruins, and other elements are combined into works of fantasy (see above). They may contain the appearance of reality, but they are not.

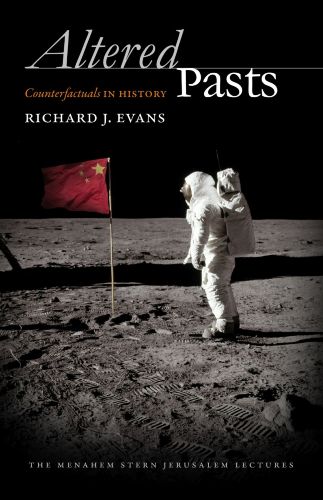

Richard Evans, in his broader takedown of Niall Ferguson's Virtual History, argues that not only do counterfactuals not restore contingency to historical narrative, they "confine it in another that in reality is far more constricting" because counterfactuals "posit a whole series of other things that would have inevitably followed" the alternate path in history.[6] For Evans the counterfactual does not help us because it assumes that there are not any more changes in the alternate timeline, and that the alternate event itself does not change subsequent events in ways that cannot be foreseen.[7] Evans also suggests that we rarely need counterfactuals to explain historical processes, because existing evidence is often enough to highlight the causation of reality.[8]

A lot of these critiques boil down to a recurring debate among historians about the role of individuals versus processes. That is, what drives change? Is it the actions that a person takes, or is it the accumulation and weight of processes? If a single person can change the future, meaning it is a malleable future, then each individual action can be explored and questioned for its role in shaping that future. If individual actions matter little, then what value is counterfactual history, or the study of the person, at all? A reasonable critique of counterfactual history is that it can repeat the older idea of "Great Man" history, essentially the idea that certain individuals have disproportionate impacts on the course of events. Of course, it would be impossible to deny the role that personalities and individuals play in history, just look at the current president of the United States, but they are not solely responsible. Counterfactuals can easily substitute personal chance for broader structural forces, but we also don't need to give in to determinism. Most historians fall in between these two extremes anyways, so some of these critiques on both sides resemble strawmen at times.

Part III: What Use is Counterfactual History?

Not quite counterfactual history, because it is postulating one possible future but Daniel Lord Smail's recent piece in the Centennial issue of Speculum, titled "2096", emphasizes the possibilities of counterfactual history nicely.[15] It portrays the future of the Medieval Academy of America and its end in the year 2083, and purports to be a report by one of the last council members writing in the year 2096 to record what happened since the present. Naturally, it is not a work of prophecy, but of warning and challenge about academic freedom and the future of the field of medieval studies. The alternate future is thus not a prophecy, but a mirror. Counterfactual history can often work in similar ways. The infamous "appeasement" critique is used as a warning in what is thought to be similar scenarios today. The questions we ask of the past, both counterfactual and factual, are grounded in our own present. Counterfactual history depends on some level of presentism: "we are either grateful that things worked out as they did, or we regret that they did not occur differently."[16]

Here is where I might disagree a bit, counterfactual history can certainly proceed from presentist concerns, but that isn't always true. It does so only if the supposed end result is something that is tied to the present. So someone may wonder what would be different if Al Gore won the 2000 presidential election, because they are dissatisfied with modern US politics. But, if we are wondering about the course of English history if the White Ship had not sunk in 1120, we are not necessarily operating from a presentist point of view (unless you are trying to draw a causal connection between the present and that event). The most tenuous counterfactuals often involve long causal chains and narratives that extend far past their origin points.

It is also worth pointing out how many of the most famous counterfactual scenarios: the beginning of World War 1, the outcome of World War 2, etc. concern modern periods, where (theoretically) there is substantially more documentation of attitudes, ideas, and policies that can be brought to bear. A counterfactual of the Middle Ages can, and must, operate on different grounds. I would instead suggest something on a much smaller scale, a "micro-counterfactual" that is not concerned with spinning an entire alternative history. Something closer to Christopher Clark's 2012 book Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. Essentially, Clark's argument is that World War I was the result of a series of choices that accrued over time to push Europe into war. Yet these choices were far from inevitable or obvious to contemporaries.

In my own dissertation I rarely describe a counterfactual explicitly, but it informed my thinking on a whole host of issues. For instance, just the simple act of interrogating: "why would Arnulf want to become emperor?" opened a new avenue of inquiry for me. I am not interested in writing an alternate history of Europe if Arnulf didn't become emperor, but instead to survey the potential choices open to him and why he chose one specific course of action. It turns what may seem obvious, of course every ruler wants to be an emperor!, into a more interesting question with a more complicated answer. It is here that I think we can find the utility of counterfactuals: not for imagining the grand sweep of history anew, but in understanding the historical agency of actors in given circumstances. It is about shaking loose our assumptions about what was "obviously" the correct or right choice, and digging deeper into what could have been, but wasn't.

Thanks for reading Among the Ruins! If you haven’t subscribed, please do so below and you can have these posts delivered right to your inbox!

- Collected Fictions, translated by A. Hurley (Penguin Books, 1998), p. 125.

- For a potted history of this approach see R. Evans, Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History (Brandeis University Press, 2013), pp. 1-30.

- See S. Kaye, "Challenging Certainty: the Utility and History of Counterfactualism," History and Theory 49, no. 1 (2010): pp. 38-57 at p. 39.

- For instance things such as "the consequent is derivable from the conjunction of the laws and an antecedent" in M. Bunzl, "Counterfactual History: a User's Guide," American Historical Review 109, no. 3 (2004): pp. 845-858 at p. 851. Not the worst language to parse, but not exactly fun and light.

- Bunzl, "Counterfactual History," p. 849.

- Evans, Altered Pasts, p. 57.

- Evans, Altered Pasts, p. 61.

- Evans, Altered Pasts, p. 117.

- C. Sunstein, "Historical Explanations Always Involve Counterfactual History," Journal of the Philosophy of History 10, no. 2 (2016): pp. 433-440.

- Kaye, "Challenging Certainty," pp. 40-41.

- D. Nolan, "Why Historians (and Everyone Else) Should Care About Counterfactuals," Philosophical Studies 163, no. 2 (2013): pp. 317-335 at pp. 320-323.

- Nolan, "Why Historians (and Everyone Else) Should Care About Counterfactuals," p. 326.

- Evans, Altered Pasts, p. 91.

- Nolan, "Why Historians (and Everyone Else) Should Care About Counterfactuals," p. 329.

- D. Smail, "2096," Speculum 101, no. 1 (2026): pp. 382-387.

- G. Rosenfeld, "Why Do We Ask "What If?" Reflections on the Function of Alternate History," History and Theory 41, no. 2 (2002): pp. 90-103 at p. 93.